This article contains a free preview of “Colonialism, Collapse, Continuity” (hereafter: CCC) by Ebne Melek.

The full book is now available at the secure link that follows.

Aside from the introduction below, this article contains only images and minimal text.

To gain a full understanding of the images, their context, significance, and additional sources and information that will make you an expert of Ethiopian studies, purchasing the full book is highly recommended.

Cover page

Intro

Regrettably, there is much confusion regarding Ethiopian history.

While many foreign authors have attempted to illuminate the matter, they have only made it more confusing.

The purpose of this book is to dispel the present myths created by this foreign literature. One popular myth can be summarized thusly:

"Since the homeland of Aksum is inhabited by Tigrinya speakers (hereafter: TS) today, the founders of the Aksumite Empire must have been the ancestors of TS."

Genetics, linguistics, and more expose the flaws in this statement.

However, this book concerns itself primarily with archaeology, perhaps the strongest form of evidence.

By studying a multitude of ancient artifacts from Ethiopia, Eritrea, North Africa, South Arabia, and beyond, I highlight the historic connections between these different regions.

More specifically, I demonstrate that, as the primary heirs of Aksum, the Amhara people exhibit the greatest level of political, cultural, and religious continuity with the rulers of that kingdom and its forerunner, D'MT.

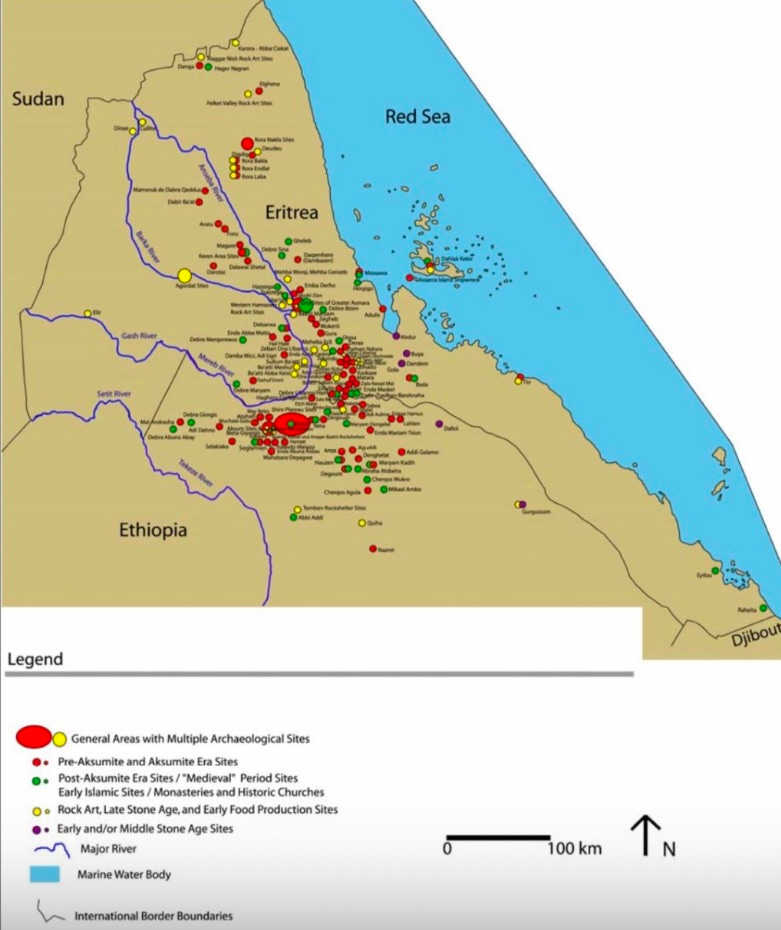

The artifacts in question are found in Fig. 1. They can be divided into three main categories:

pre-Aksumite sites, containing mostly inscriptions and engravings, represented by red;

Aksumite-era sites, generally consisting of inscriptions and engravings, also in red; and

post-Aksumite structures, represented by green.

As a kingdom, Aksum was born at the outset of the 1st century AD. It succeeded D'MT, a much older kingdom ruled by the same people.

The early 3rd century Persian philosopher Mani described Aksum as such:

“There are four great kingdoms on earth: the first is the kingdom of Babylon [Mesopotamia] and Persia; the second is the kingdom of Rome; the third is the kingdom of the Axumites; the fourth is the kingdom of the Chinese.”1

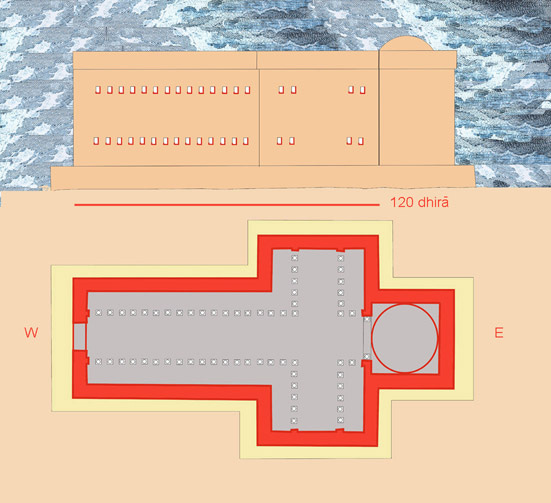

Based on Monumentum Adulitanum II, inscribed in Greek by an unnamed Aksumite king on a throne in the coastal colony of Adulis, the dominion of Aksum resembled Fig. 2. in the 3rd century.

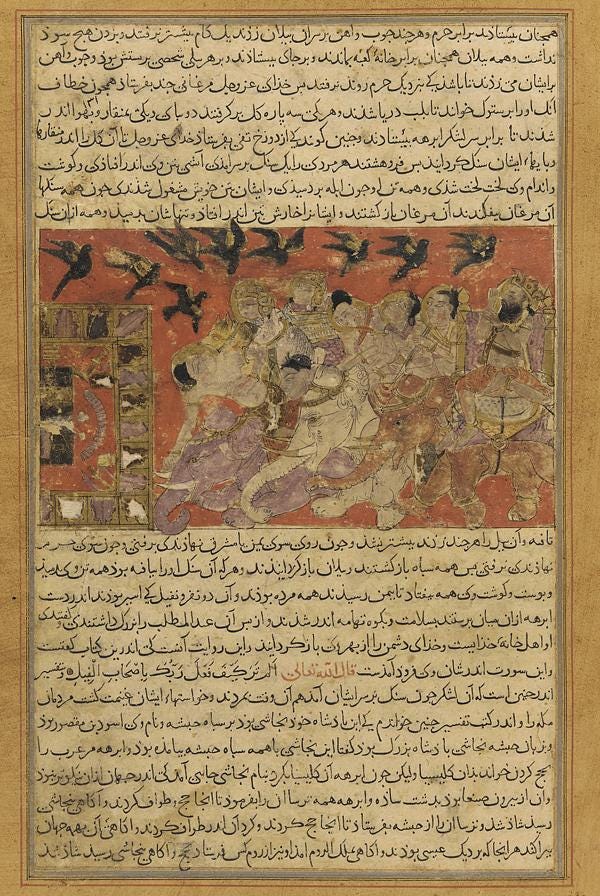

In the early 7th century, persecution by Middle Eastern pagans forced the earliest Muslims to migrate from Arabia to Ethiopia for asylum.

Some 15 refugees arrived in Aksum circa 615, one of them being al-Zubayr.

He documented a failed rebellion against the king, likely named Armah, who reigned around this time:

"While we were living thus, a rebel arose to snatch his kingdom from him, and I never knew us to be so sad as we were at that, in our anxiety lest this fellow would get the better of the Negus, and that d man would arise who did not know our case as the Negus did. He went out against him, and the Nile lay between the two parties. The apostle's companions called for a man who would go to the battle and bring back news, and al-Zubayr b. al-'Awwăm volunteered. Now he was the youngest man we had. We inflated a waterskin and he put it under his chest, and swam across until he reached that point of the Nile where the armies faced one another. Then he went on until he met them. Meanwhile we prayed to God to give the Negus victory over his enemy and to establish him in his own country; and as we were doing so, waiting for what might happen, up came al-Zubayr running, waving his clothes as he said 'Hurrah, the Negus has conquered and God has destroyed his enemies and established him in his land.' By God, I never knew us to be so happy before. The Negus came back, God having destroyed his enemy and established him in his country, and the chiefs of the Abyssinians rallied to him. Meanwhile we lived in happiest conditions until we came to the apostle of God in Mecca."2

Nevertheless, domestic turmoil was far from over. By the 8th century, the rise of Islam in the east and encroachments on Aksum’s coastal possessions resulted in a severe decline in trade.

Around the same time, the political centre of Aksum came under attack by various entities—from the north, Arabized Bejas; from the south, more Cushitic pagans.

Much of the Aksumite ruling class began to migrate south in this period, permanently settling in the Amhara region—contrary to insinuations that it remained in place or simply “disappeared” into thin air. That is why:

Multiple 9th century sources report a southward shift of Aksum’s royal capital, with the scholarly consensus pointing somewhere between Bete Amhara and Shewa (see Fig. 3.).

Given its colossal importance in Ethiopian history, the event is referred to as the Great Migration, or ታላቁ ስደት (talaqu sədät).

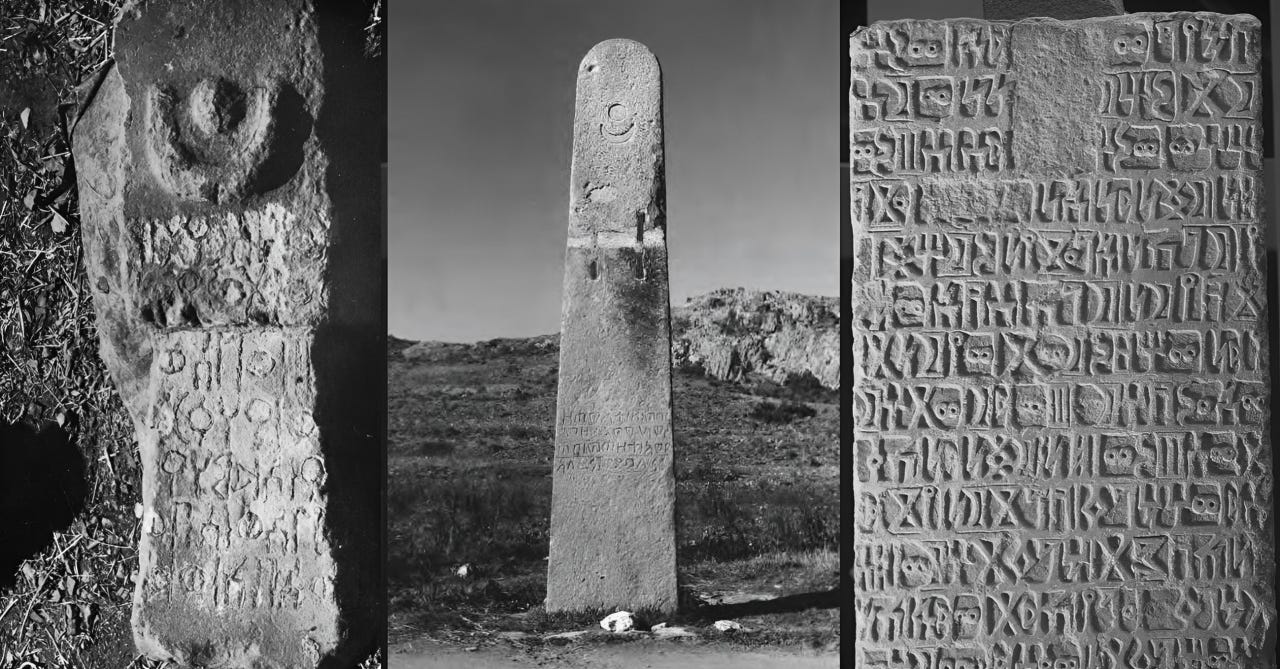

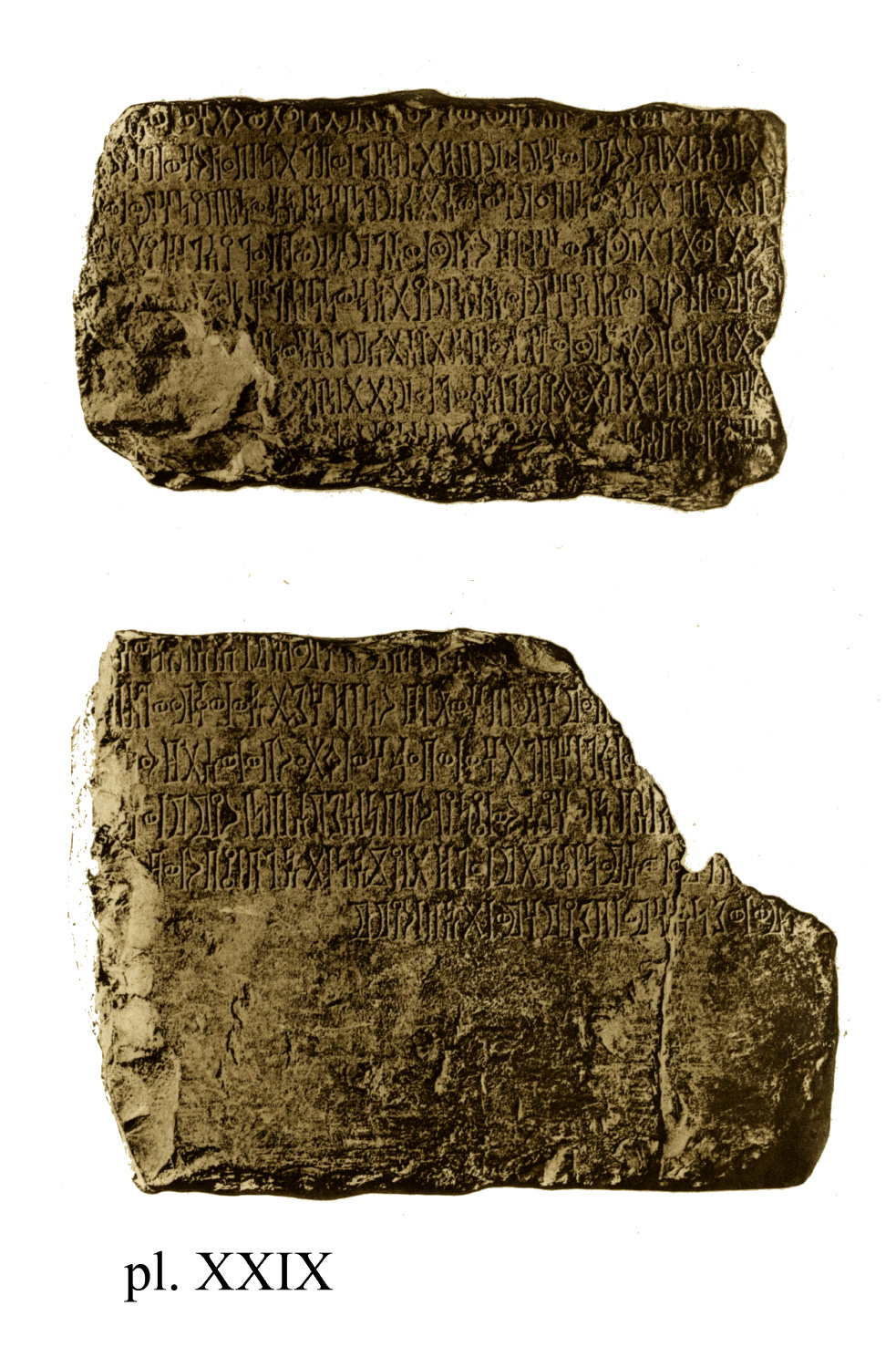

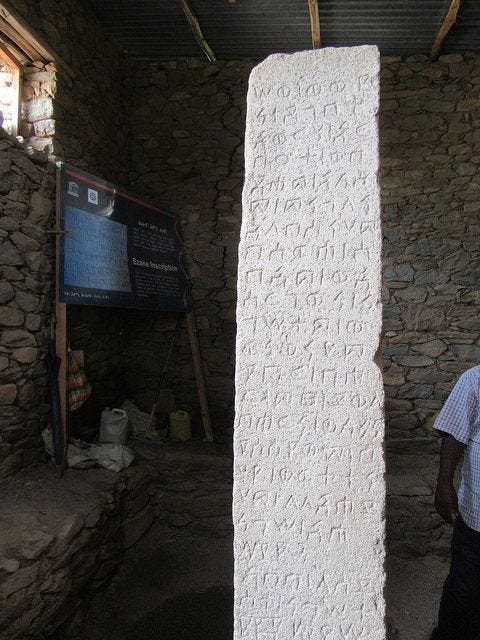

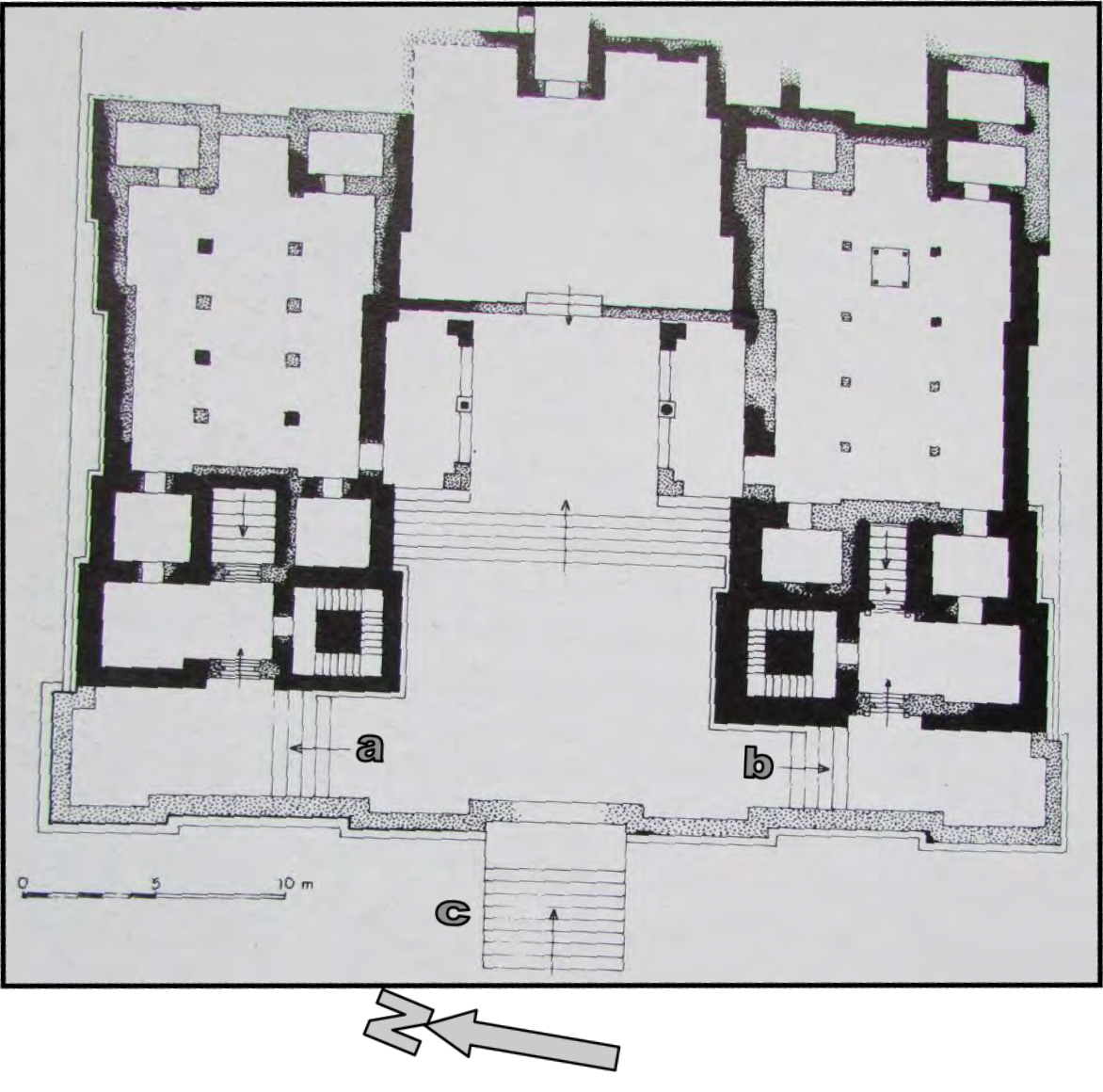

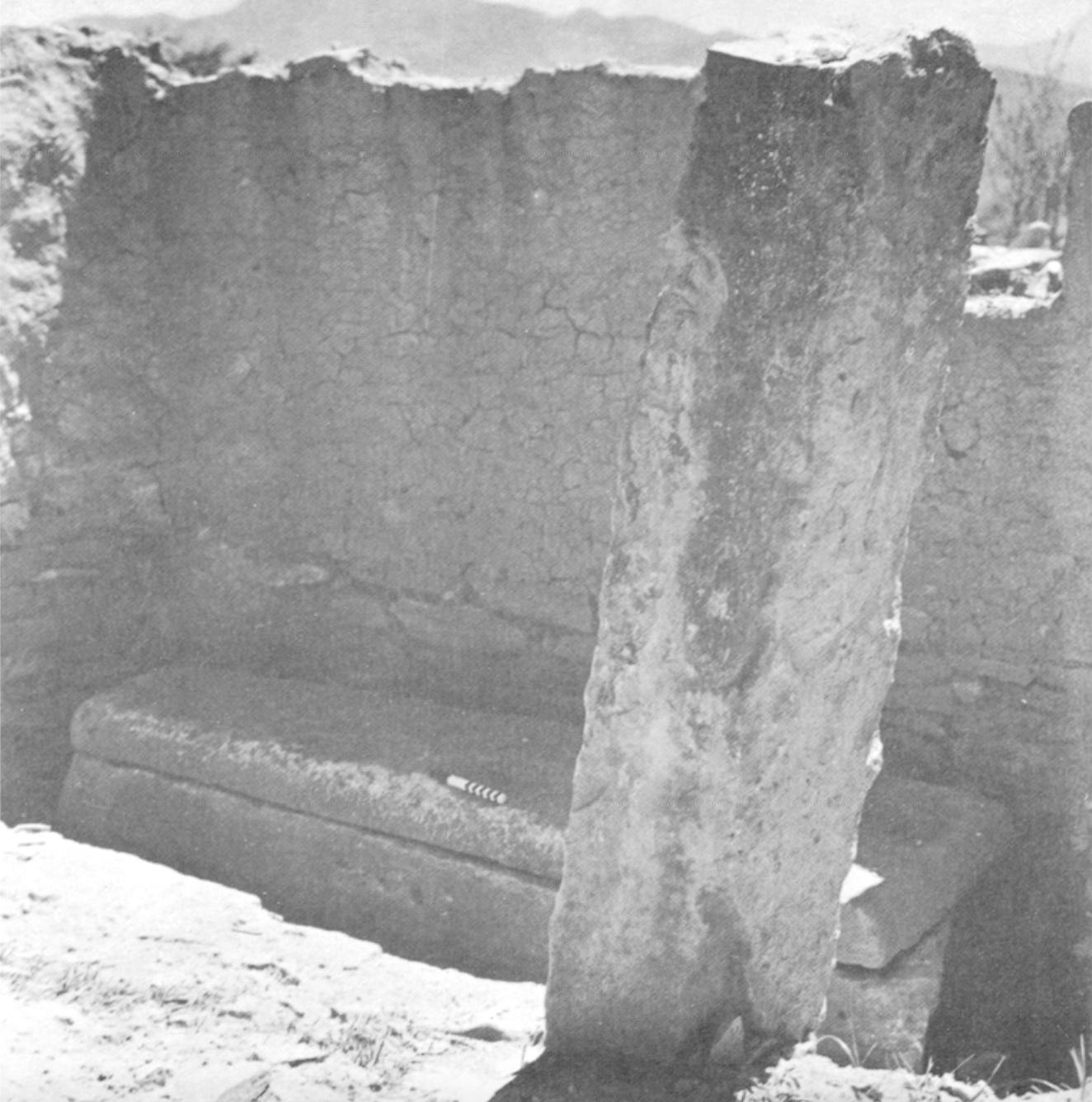

An Aksumite warlord named Daniel, one of the few Amharas still in Aksum, describes in a late 9th century inscription more enemies invading his land (Fig. 4.).

He adds that the King of Aksum was not actually in Aksum. Instead, he had moved his capital south before temporarily returning to Aksum.

This inscription is consistent with the claims of the Islamic historians above. It is also consistent with ancient Ethiopian manuscripts written by Amharas about the rise and fall of Aksum.3

An early 10th century letter of an Aksumite King to King George Il of Nubia tells of his persecution by a pagan queen from the south.

Two important passages read as follows:

a) “In his (Philotheos') days, the king of Abyssinia (al-Habasah) sent to the king of Nubia (an-Nbah), a youth whose name was George (Girgis), and made known to him how the Lord had chastened him, he and the inhabitants of his land.”

b) “It was that a woman, a queen of Bani al-Hamwiyah, had revolted against him and against his country. She took captive from it many people and burned many cities and destroyed churches and drove him (the king) from place to place.”4

A 10th century letter documents the gifting of a zebra by an illegitimate Queen of Ethiopia to a ruler in Yemen.

Scholars call her “illegitimate” because she is not documented in any Ethiopian regnal list and was most likely Yodit, the woman who destroyed Aksum by 940 AD. Part of the letter reads:

“Ishãq b. Ziyad,' ruler (sähib) of Yemen, gave 'Izz al-Dawlah Abi Mansür, in the year 359 [970 AD], a gift that contained... a huge female zebra, the size of a mule, having a round rump, and ears like those of a mule. Its entire body was striped in the most beautiful and wonderful way. It is said that the zebra came from a region in Abyssinia ruled by a woman. The distance between this [region] and Baghdad is one thousand eight hundred parasangs.”5

Now, let’s return to the map in Fig. 1.

Although hundreds of Ge'ez and Sabaic inscriptions and engravings were made on various objects in Tigray and Eritrea during the pre-Aksumite and Aksumite periods, after Aksum collapsed—and the majority of its Amhara ruling class migrated south—this number was effectively reduced to zero.6

To date, there has not been discovered a single post-Aksumite inscription made by locals in Tigray, which was once the heartland of the kingdom.78

As for the green dots on the map, they represent churches or monasteries, which have similarly misleading histories. But that is a topic for another work and for another day.

For now, let us get to the meat of the problem:

Despite having roughly 1,000 years to do so, the present inhabitants of Aksum could not reproduce any of the pre-Aksumite and Aksumite artifacts therein, because they did not produce any of them in the first place.

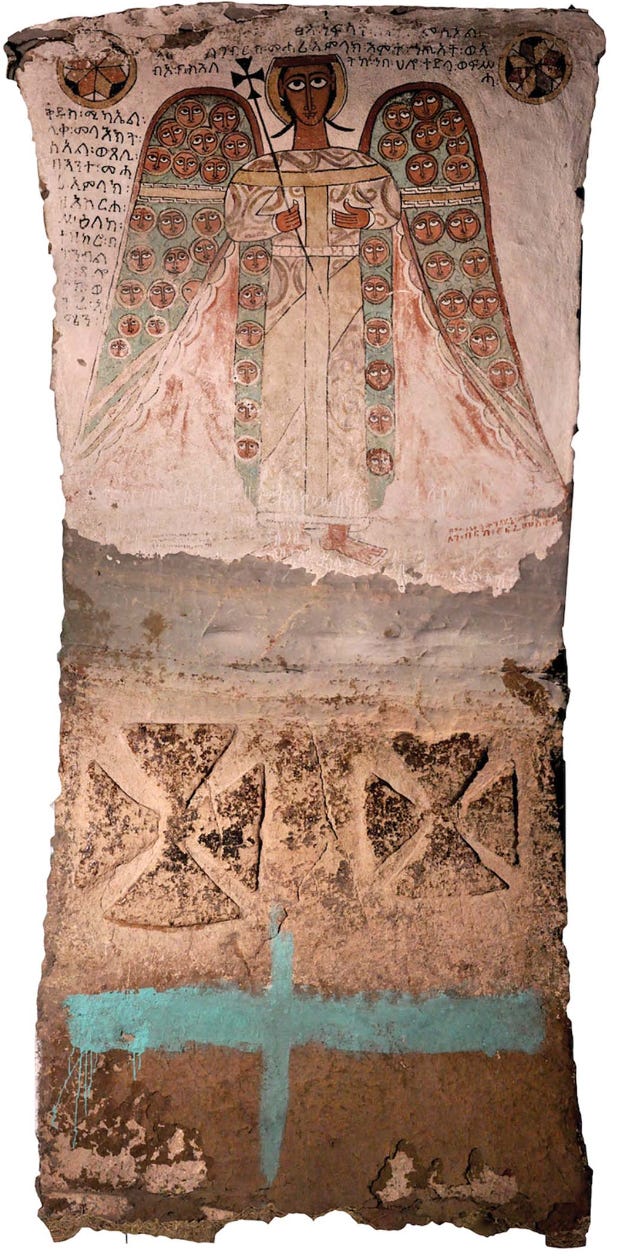

Meanwhile, the Amhara people have reproduced virtually every kind of pre-Aksumite and Aksumite structure in the same duration of time, serving as the greatest indication of their Aksumite descent.

To summarize the results of my scholarly research, I have produced the diagram in Fig. 5.

If you have not done so already, I invite you once again to order the book at the secure checkout link below.

CCC contains roughly 100 pages and over 20,000 words.

In support of the foregoing claims, the book:

Features 51 chapters of critical information about the relevant kingdoms

Presents about 150 unseen archaeological exhibits

Cites sources in Ge’ez, Amharic, Sabaic, Arabic, Persian, Greek, and more—from manuscripts, inscriptions, and other artifacts dating back over 3,000 years.

It is the first book of its kind to be written.

The author, Ebne Melek, has been hailed as “top class” and “revolutionary.”

But Ebne Melek has also been subjected to insults and threats, some very serious.

Overcoming every obstacle, Ebne Melek has published this book for you to read.

Now, let the fun begin.

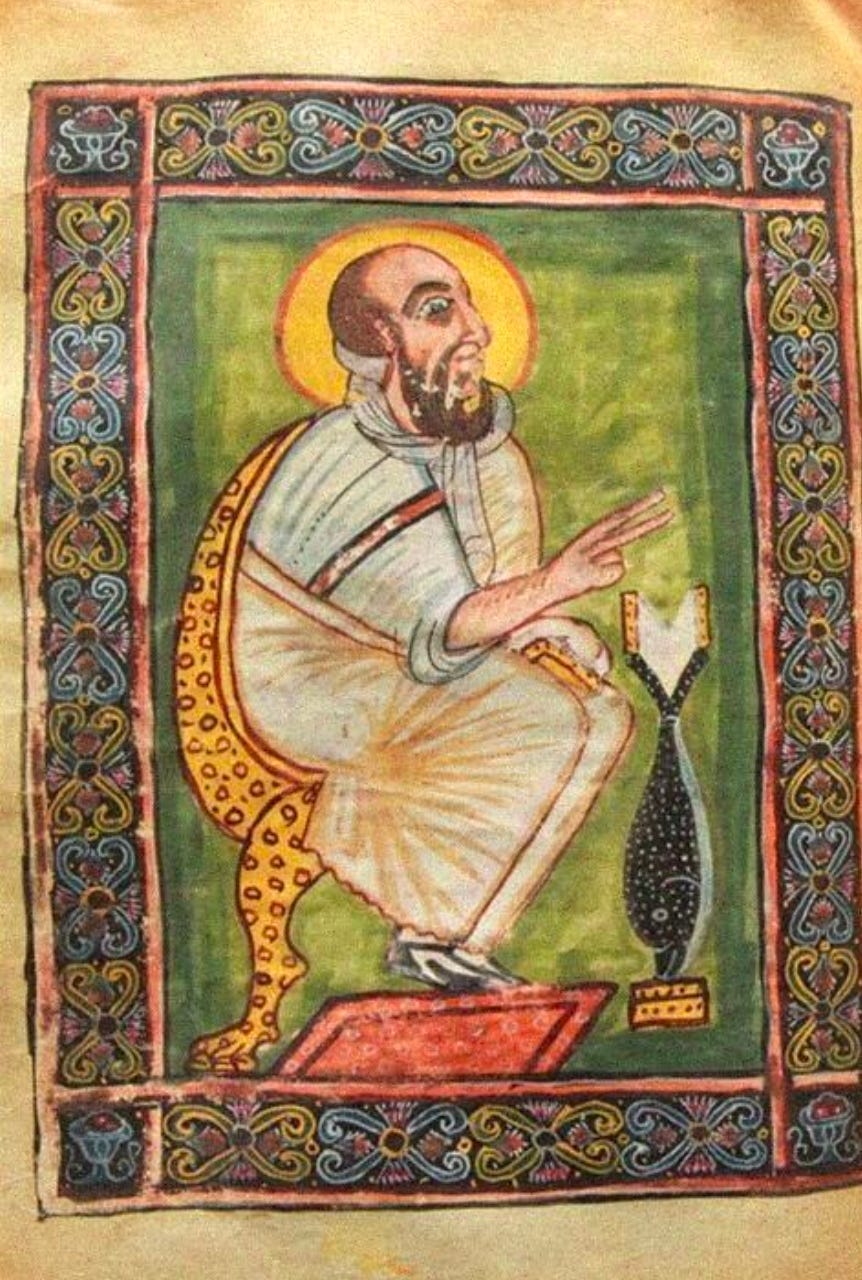

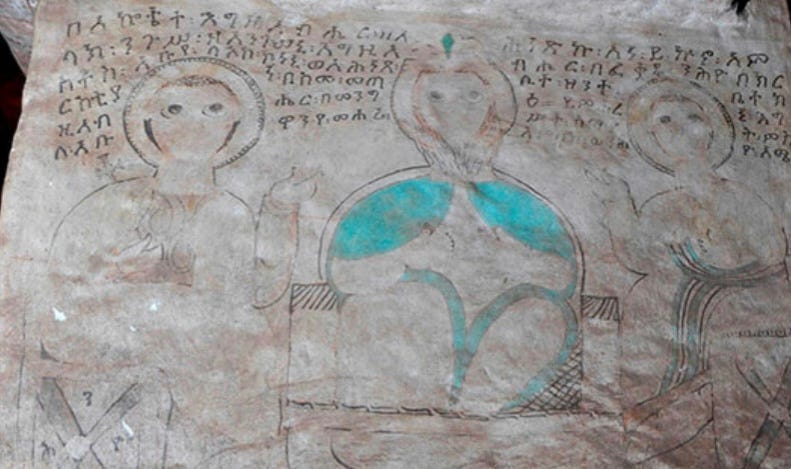

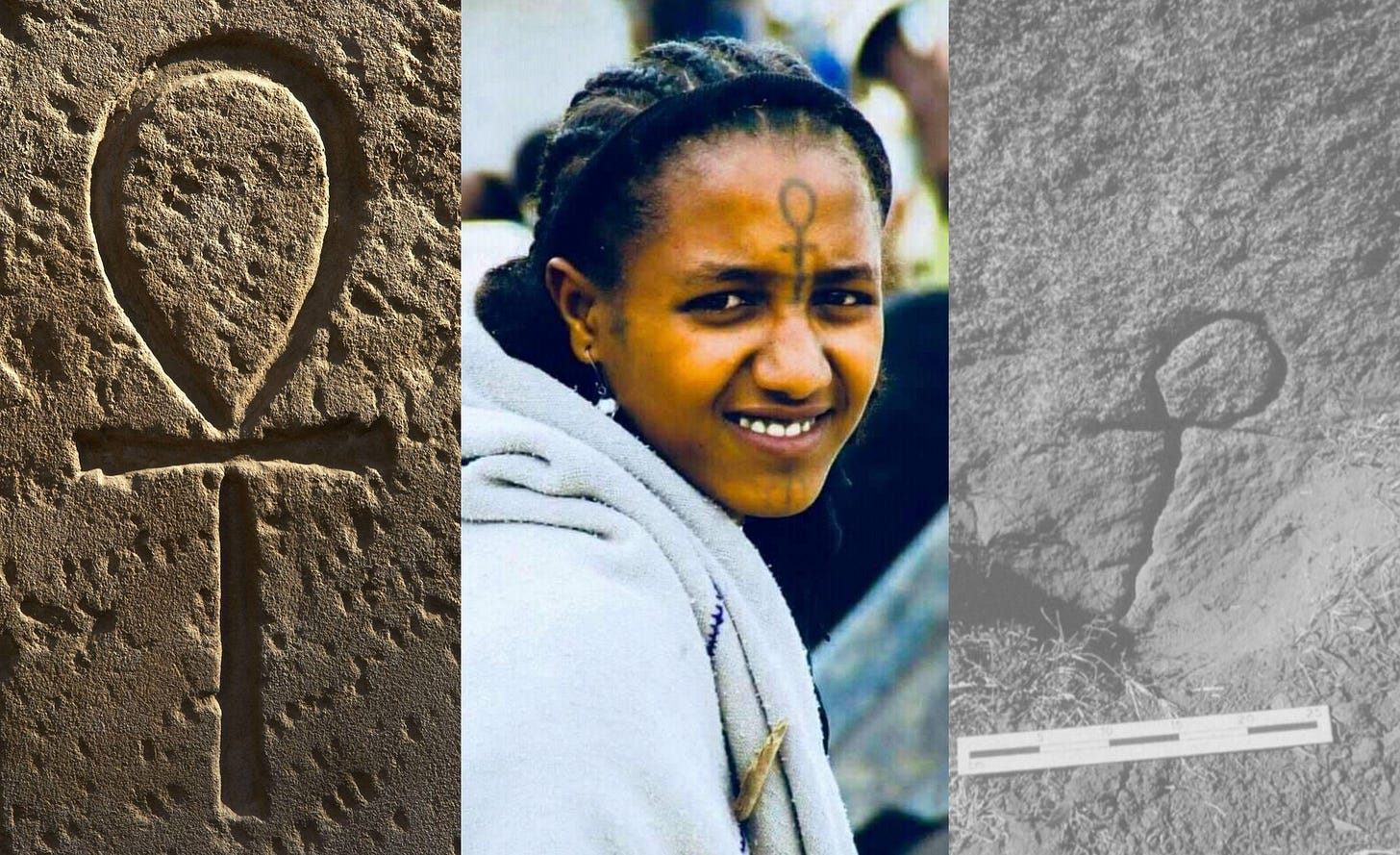

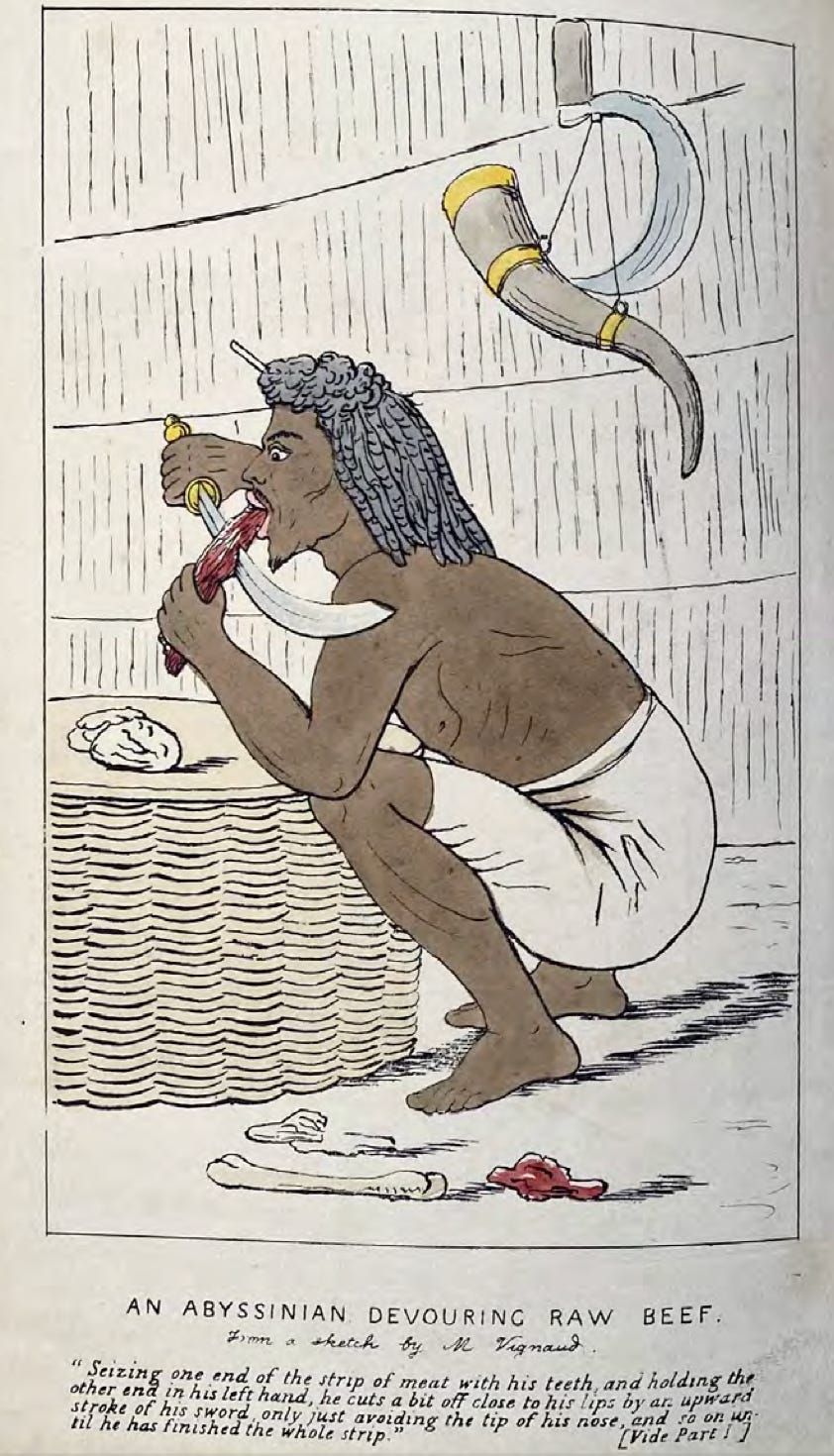

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Figs. 11-13

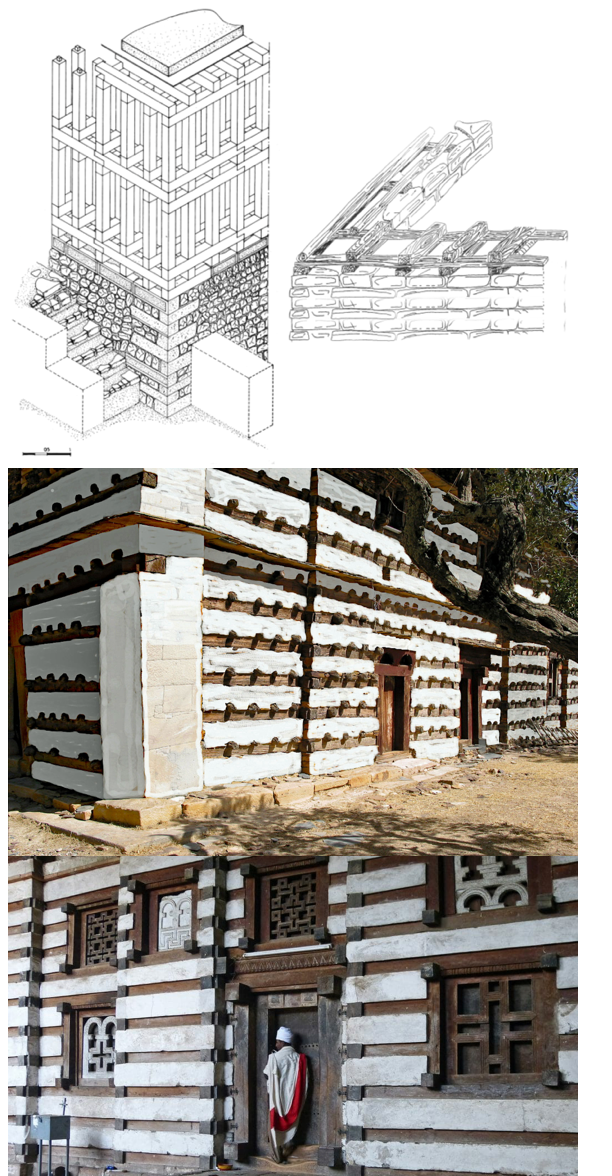

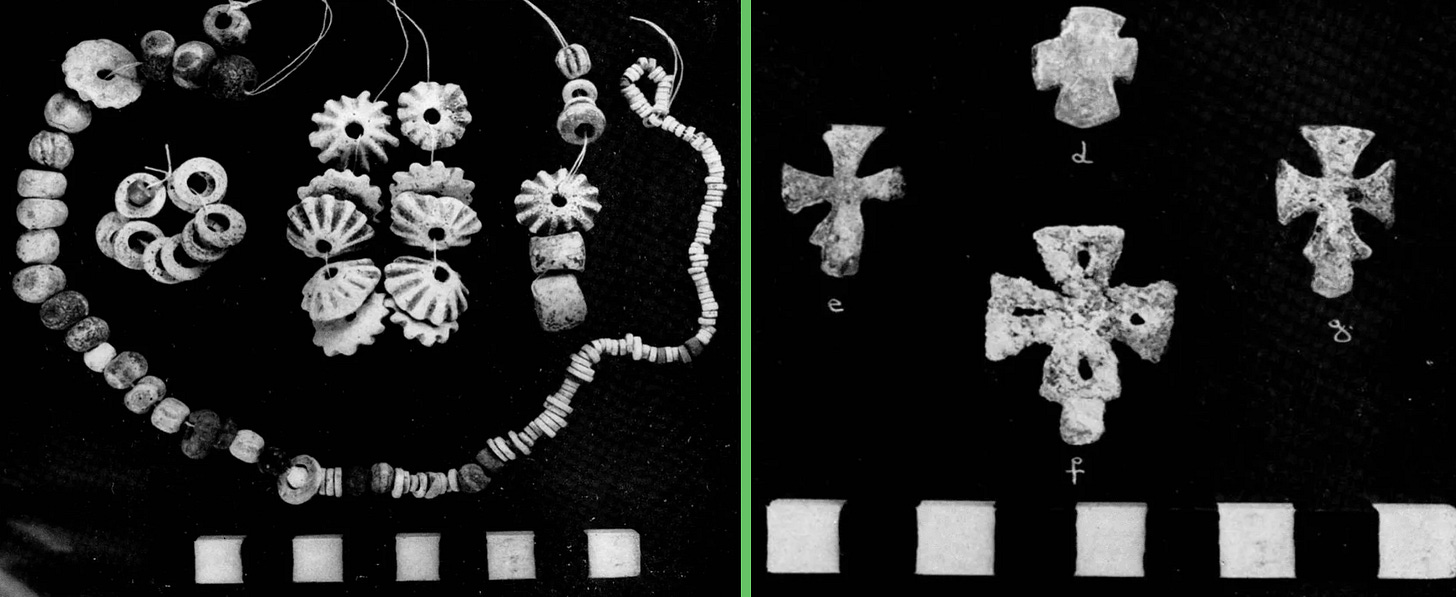

Figs. 14-17 (L-R)

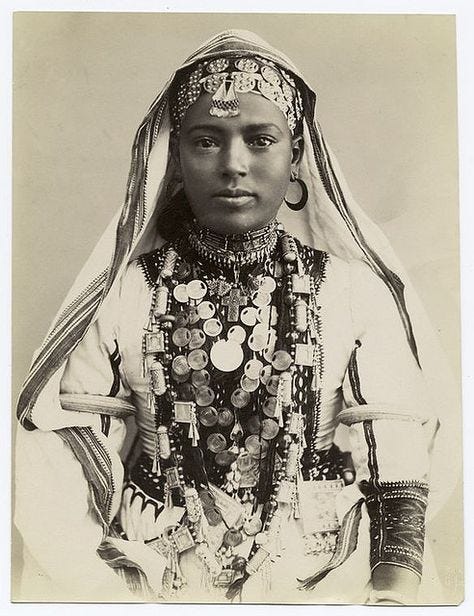

Figs. 18-19

Figs. 20-22

Figs. 23-25

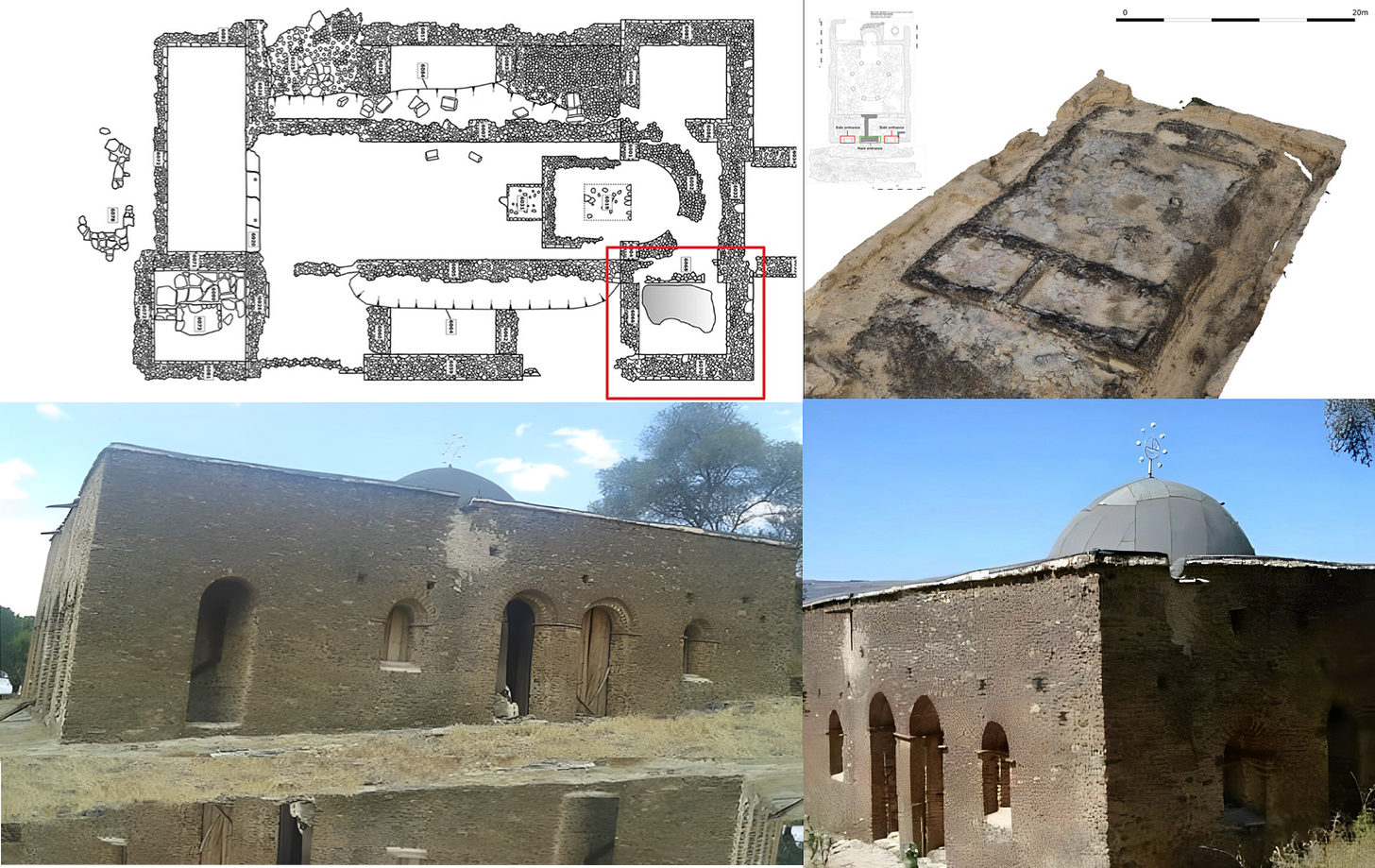

Figs. 26-29

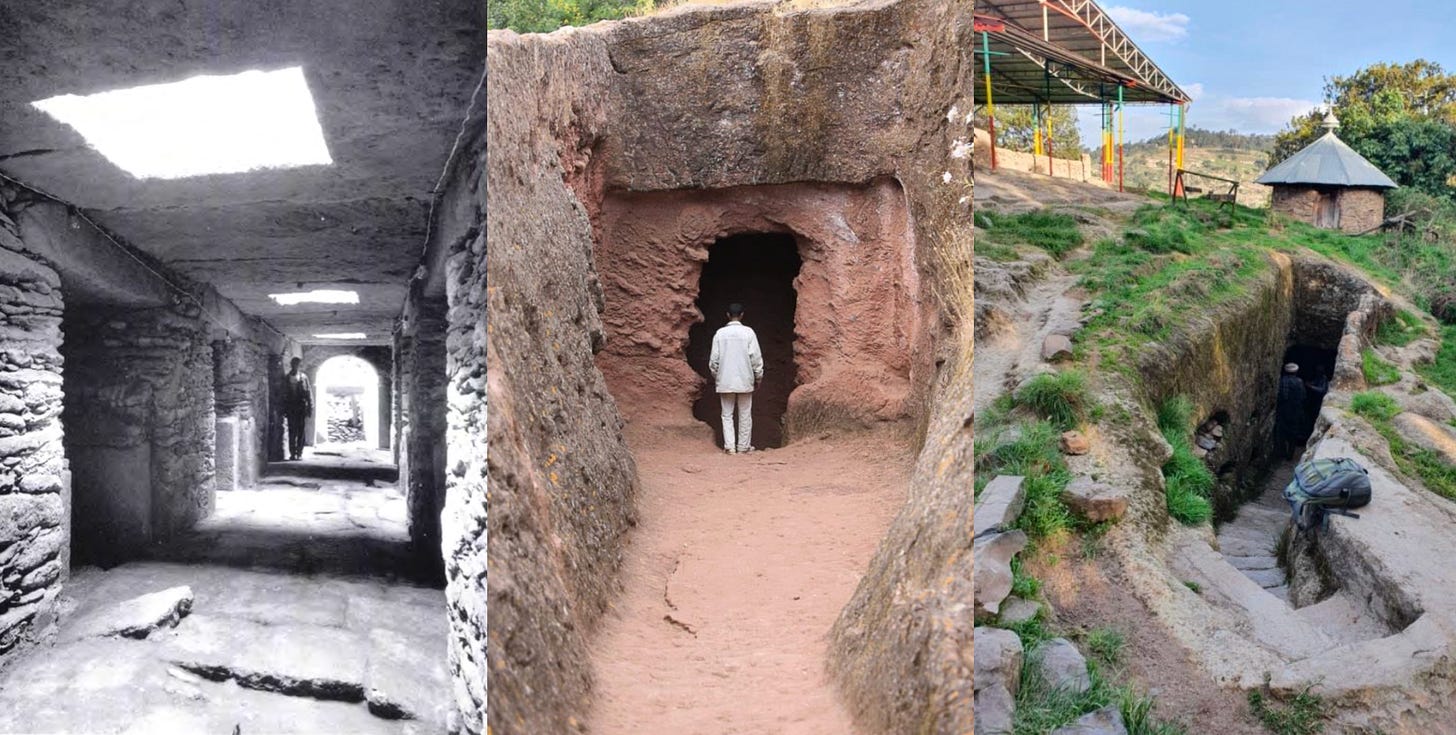

Figs. 30-32

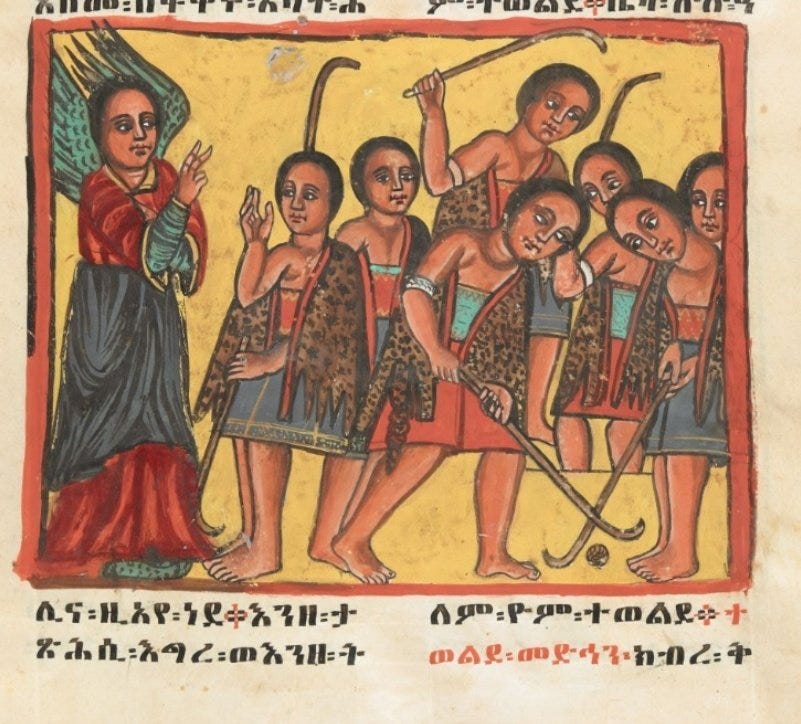

Fig. 33

Figs. 34-37

Figs. 38-39

Figs. 40-42

Figs. 43-44

Fig. 45

Fig. 46

Fig. 47

Fig. 48

Figs. 49-50

Figs. 51-52

Figs. 53-54

Fig. 55

Fig. 56

Figs. 57-59

Figs. 60-61

Figs. 62-65

Fig. 66

Fig. 67

Figs. 68-69

Figs. 70-71

Fig. 72

Fig. 73

Fig. 74

Figs. 75-76

Figs. 77-78

Figs. 80 and 79

Fig. 81

Figs. 82-83

Fig. 84

Fig. 85

Fig. 86

Figs. 87-88

Figs. 89-92

Fig. 93

Fig. 94

Fig. 95

Fig. 96

Fig. 97

Fig. 98

Fig. 99

Fig. 100

Fig. 101

Fig. 102

Fig. 103

Fig. 104

Fig. 105

Fig. 106

Fig. 107

Fig. 108

Fig. 109

Fig. 110

Figs. 111-112

Figs. 113-116

Fig. 117

Fig. 118-119

Fig. 120

Fig. 121

Fig. 122

Fig. 123

Fig. 124

Fig. 125

Fig. 126

Fig. 127

Fig. 128

Figs. 129-130

Fig. 131

Fig. 132

Fig. 133

Fig. 134

Figs. 135-136

Figs. 137, 139, and 138

Figs. 140-141.

Fig. 142

Figs. 143-144

Figs. 145-146

Fig. 147

End of free preview.

For the remaining half of the book, visit the secure link below.

“The Gospel of the Prophet Mani,” p. 148. Edited by Duncan Greenlees.

Ibn Ishaq (c. 704-768), “The Life of Muhammad,” p. 153. Translated by A. Guillaume.

መጽሐፈ፡አክሱም ( “Book of Aksum”). Edited by Carlo Conti Rossini.

According to “The History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria.” As recorded by Professor Benjamin Hendrickx in, “The Letter of an Ethiopian King to King George II of Nubia.

Aḥmad ibn al-Rashīd Ibn al-Zubayr (c. 1071), “Book of Gifts and Rarities,” p. 102-3. Translated by Ghāda al Hijjāwī al-Qaddūmī. Scholars like Mohammed el-Chennafi are also certain this passage refers to Queen Yodit. See “Mention nouvelle d’une ‘reine éthiopienne’ au Ive s. de l’hégire/Xs. ap. J.C.” for more.

Annamaria De Santis and Irene Rosi (2018), “Crossing Experiences in Digital Epigraphy: From Practice to Discipline,” ch. 6, “Inscriptions from Ethiopia,” pp. 85-86 by Alessandro Bausi and Pietro Liuzzo.

Edward Lipinsky (1997), “Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar,” p. 84.

Philip Briggs (2012), “Ethiopia: the Bradt travel guide, ” p. 16.

Tarik melalash keep it up 💪🏽

Truly amazing and informative