Introduction

As it happens, one of the oldest pieces of Ethiopia, and indeed Africa, is found in the Middle East—specifically, Israel.

That “piece” is the ancient monastery of Dayr al-Sultan (Arabic: دير السلطان ; Ge’ez: ዴር ሥልጣን; literally: “Monastery of the Sultan”), situated on the roof of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

It has been the source of a long dispute between Egyptian and Ethiopian Christians, with each side claiming to be the rightful owner.

Below, we consider the evidence together—but first, some context.

Contrary to popular belief, the existence of Ethiopians in the Holy Land is not a modern phenomenon.

The community has maintained one of the longest continuous Christian presences there.

In the letters of St. Paula and St. Eustochium, dated circa 386 AD, Ethiopian pilgrims are described as daily visitors to Jerusalem.1

While it is tempting think “Ethiopian” here refers to inhabitants of Sudan and other lands closer to Egypt, since the time of King Ezana of Aksum (c. 330 AD), the country has been known to locals as “Ethiopia.”2

Foreigners, such as the 4-5th century Graeco-Roman writer Philostorgius, also referred to the Aksumites as “Ethiopians.”3

The same is true for the 6th century Graeco-Egyptian traveler Cosmas Indicopleustes, who called the King of Aksum “the King of Ethiopia.”4

Around 312 AD, Roman Emperor Constantine accepted Christianity.

In year 325, he commissioned the construction of an important church.

By year 340, Bishop Maximus of Jerusalem dedicated that church at the foot of Mount Zion, where Christ and his disciples enjoyed the Last Supper.5

In 518, pilgrim Theodosius confirmed the existence in Jerusalem of the church of “Holy Zion, the Mother of all Churches: [the] Zion our Lord Christ founded with the apostles.”6

Today, it is commonly referred to as “The Church of the Holy Sepulchre.”

Those who have read “Colonialism, Collapse, Continuity” know that c. 520 AD, King Kaleb built in Aksum a church immediately following his successful crusade in Jewish Yemen.

He named it after the one in Jerusalem—Zion (ጽዮን or s'əyon)—and dedicated it to St. Mary, እመ ብዙሃን (ʾəmä bəzuhan; “Mother of the Masses”).

Like the one in Jerusalem, Aksum’s Zion is considered “the Mother of all Churches” in Ethiopia.

Based on a centuries-old manuscript tradition, King Kaleb climbed atop a mountain, where the ideal site for Mariam Zion’s construction was revealed to him. 7

He subsequently named that mountain ምክያደ እግዚአነ (məkəyadä ʾəgəziʾänä), meaning “footprint of Our Lord.”

Likewise, around 670 AD, Frankish churchman Arculf of Gual visited the Holy Land, where he also described “a footprint of the Lord” on the Mount of Olives.8

The Ethiopian Synaxarium tells that at the end of King Kaleb’s reign, he shipped his crown to Jerusalem and retired to a monastery.9

Some 30 years later, an anonymous pilgrim from Piacenza, Italy visited the Holy Sepulchre Church and observed, hanging from its walls, “emperors crowns” akin to those sent by Kaleb.10

Beyond bearing the same name, at construction, Ethiopia’s Mariam Zion was “identical in both layout and proportion” to its Jerusalemite counterpart.11

Scholars tell that both are five-aisled basilicas that initially had seven chapels, with this number since being expanded.

Historic records produced by Armenians and Ethiopians respectively tell that the two had similar proportions: 125:92 cubits for Aksum’s church, compared to 100:75 cubits for Jerusalem’s.12

There is no record of foreigners participating in the construction of Aksum’s Zion.

So lest we believe these parallels to be mere coincidences, one must wonder whether Ethiopians contributed to the founding of the Holy Sepulchre Church.

That, or Ethiopians based their Zion Church on familiarity with the layout and history of the former.

By the 7th century, Muslims had conquered Jerusalem.

While it is tempting to think this event spelt the end of Christian presence there, the opposite is actually true.

Omar ibn al Khattab, leader of the conquering Islamic army, immediately issued a decree in which he recognized “the Habash” (an exonym for all inhabitants of historic and modern Ethiopia) as an established community in Jerusalem.13

Although other Christian communities were present, as you will soon learn, Ethiopians were treated like VIPs……… Yes, Very Important Persons.

Before that, let us hear the Coptic side of the story.

According to the Copts, in year 384, four Egyptians known as the Tall Brothers “went to Jerusalem as a result of a dispute between them and their bishop, Theophilus of Alexandria.”14

While the existence of these monks is documented, most evidence suggests they went to Palestine generally, not Jerusalem specifically.

In 1092, Mansur al-Tilbani was appointed as Governor of Jerusalem.15

Although he was Christian, claims that Mansur originated from Egypt remain unsubstantiated.

In year 1165, Coptic and Ethiopian presence in Jerusalem was noted by German pilgrim Johann von Würzburg.16

Crucially, his records indicate that, at the time, only the Ethiopians possessed and maintained a chapel.

In year 1236, the Coptic Diocese of Jerusalem was established under Pope Cyril III.17

External primary sources are lacking, but we will accept this claim on the basis of earlier accounts of Coptic presence in Jerusalem.

Backtracking a bit, after overcoming European Crusaders, in 1187, Salah ad-Din (or Saladin), supreme ruler of Ayyubid Egypt, restored Islamic control over Jerusalem.

He is known to have been kinder to the Christians of Jerusalem than his Muslim—and some Christian—predecessors.

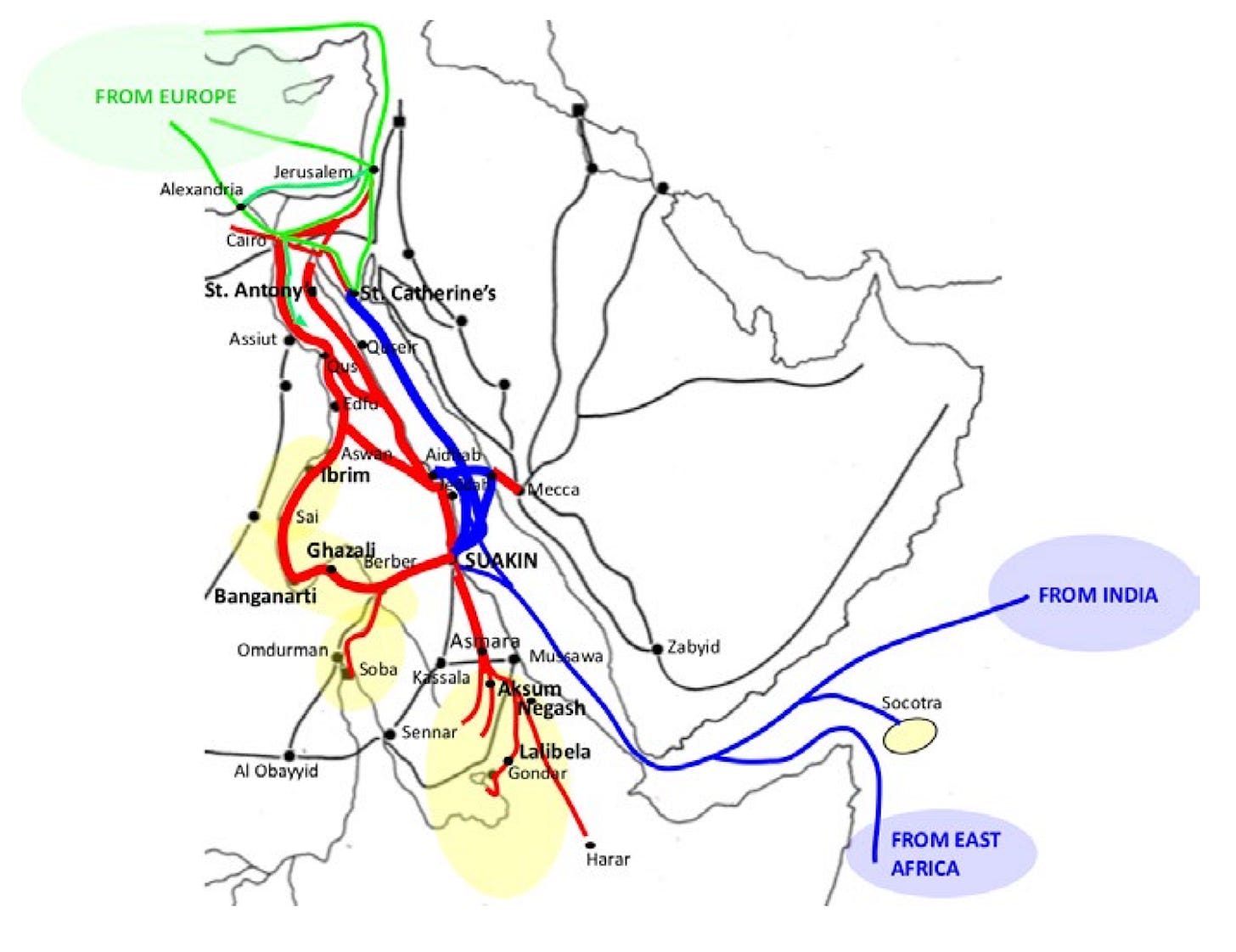

In fact, Saladin invited pilgrims from all over the Christendom to the Holy City, as illustrated in the map below.18

On their way to Jerusalem, Ethiopian Christians stopped in Egypt and prayed in local monasteries, such as the Syrian Dayr al-Suryan Monastery.

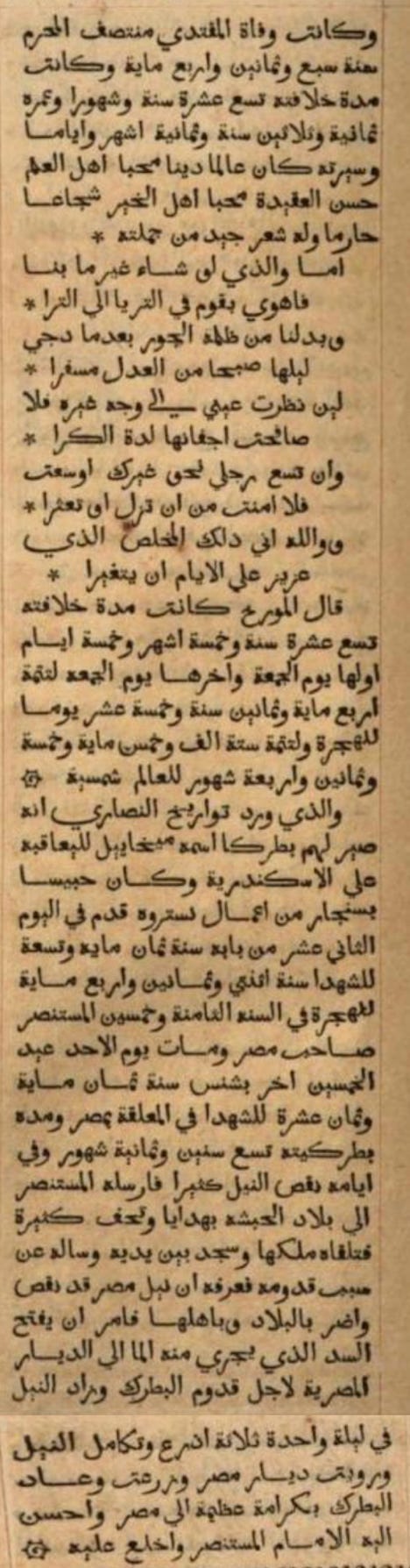

This is evidenced by Ge’ez writings on manuscripts therefrom, just like the 12th century one below.

They are found alongside writing in Coptic, Syriac, Arabic, and Armenian.

Now, pertaining to Dayr al-Sultan specifically.

I will warn you: this is where things get contentious.

Copts claim that the monastery was gifted to them by the 7-8th century Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan.19

However, as the evidence presented thus far shows, Copts did not have a known presence in Jerusalem until the 12th century, meaning this latest assertion is both baseless and improbable.

Copts further claim that Saladin affirmed their ownership over Dayr al-Sultan.

Yet, whereas Copts were subjects of Egyptian Muslims—who not only viewed them with suspicion but actively persecuted them—Ethiopians were, for lack of a better term, their “masters.“

Perhaps ironically, proof for this claim comes from a Copt himself—Jirjis al-Makī (1206-1280 or 1293), a well-respected Egyptian historian.

He recorded that the powerful sultans of Ayyubid Egypt, including Saladin himself, had a tradition of paying tribute (i.e., taxes and gifts) to the Ethiopian monarchs. More on that in this article.

This tradition contributed to the VIP status of Ethiopians in the Holy Land, not just during Saladin’s time but centuries afterward.

Thus, if any community received the sultan’s favour—including Dayr al-Sultan Monastery as a gift—it must have been the Ethiopians.

Before moving on, note that claims #15 and #16 above, made by Copts today, are exactly the same claims made by Ethiopians—and corroborated by foreigners—some 150 years ago.

As you will soon see, such “narrative theft” is part of a much larger and darker trend.

In the 16th century:

“Germanos, the Greek Orthodox patriarch in Jerusalem, writing to Ivan the Terrible in 1559, compared his own status and the condition of his sect unfavorably with that of the Armenians and Copts.”20

That means Ottomans gave Copts preferential treatment over Greeks.

However, no matter how well Ottomans treated Copts, they never treated them better than they treated Ethiopians.

As one scholar explains:

“During those years when the Christians of Jerusalem were closely supervised by the Muslims, the Ethiopians enjoyed certain privileges to which others were not entitled… the Sultan allowed them to move freely in the Holy Land with symbols of their Christian identity, such as the Cross, uncovered. Most contemporary writers associated the enjoyment of these privileges by the Ethiopians with the importance to Egypt of the Nile River that originates mainly from the Ethiopian highlands.”21

More on the Nile in this article.

The next example illustrates the deceptive nature of Coptic claims.

To quote Coptic Archbishop Basilios:

“The connection between the Ethiopians and the monastery began when they were invited to stay there as they needed a shelter after they lost their monastery of Mar Ibrahim and some other holy places in Jerusalem in 1654, when they were unable to pay their taxes.”22

However, modern scholars, drawing on historic tax records, confirm that “Jerusalem’s Ethiopians never constituted a tax-paying community.”23 The reason is because Ethiopians were there for purely religious purposes—not political ones like some others.

Ottoman authorities understood this well, and that is why the 20 Ethiopians recorded in the city’s legal register for years 1562-63 were all tax-free clergymen.24 There is no evidence this tax-free status was revoked abruptly at any point. On the contrary, it was upheld by successive Ottoman sultans.

This is confirmed by decrees (“firman”; plural, “firmen”) by Sultan Selim I (c. 1512-1520), Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (c. 1520-1566), and Sultan Ahmad (c. 1603-1617).25

Ottoman rulers documented some of the other properties owned by Tewahedo Christians.

Their firmen state that, among other things, the Ethiopians possessed four chapels inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, as well as the Dayr al-Sultan Monastery.26

What were these specific chapels owned by the Ethiopians?

Chapel of St. Mary of Golgotha

Chapel of St. Michael

Chapel of the Opprobrium

The existence of a fourth Ethiopian chapel is mentioned but remains unnamed. Some scholars suggest it was located “in the rotunda of the Holy Sepulchre.”27

Later sources, and scholars, list the Ethiopian chapels as:

Chapel of Our Lady and of St. John the Evangelist;

Chapel of St. Michael;

Chapel of St. John the Baptist; and

Chapel of St. Mary Magdalene28

A modern layout of the church is found below.

Additional confirmation comes from the year 1347, when Niccolo of Poggibonsi wrote that the Ethiopians owned the Chapels of St. Mary of Golgotha and St. Michael.29

Other Ethiopian assets are also documented therein, such as the altar of St. Joseph in the Church of Nativity (found in Bethlehem) and an altar in the Garden of Gethsemane, Jerusalem.

The next example represents an unseemly case of gaslighting.

According to Coptic Archbishop Basilios:

“Under Turkish rule, despite the Copts' generosity and hospitality toward them, the Ethiopians soon turned against their hosts and attempted to obtain rights in the monastery. These attempts were in vain, but in 1878 the keys of the church were stolen.”

All the information I have quoted from Coptic authorities comes from a series of documents published in 1991.

I mention “gaslighting” above because everything the Coptic Bishop just accused Ethiopians of doing—unequivocally, in year 1991—Ethiopian monks accused Copts of doing roughly 110 years prior.

So not only have some Coptic officials been fabricating stories about a monastery they never owned, they have also been mocking the same Ethiopian Christians they robbed of their property.

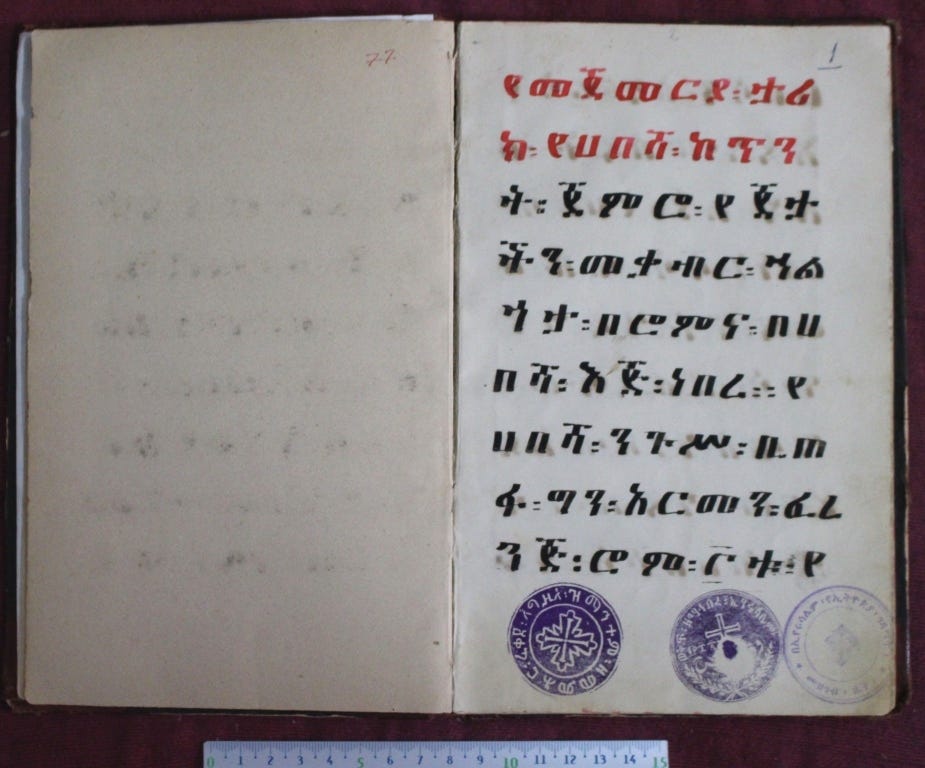

We have evidence from an Amharic manuscript written in Jerusalem between 1890 and 1906 by Ethiopian monk Welde Medhen (Ge’ez: ወልደ መድኅን ; wälədä mädəhən; “Son of the Saviour.”30

I quote relevant passages below, alongside external sources in support:

In 1821:

“Before King Tewodros came to power [in Ethiopia], 34 years [earlier], there were 58 monks who lived in Jerusalem, in Dayr al-Sultan, the Ethiopian monastery… After that, at that time an Egyptian called Abraham Juhari came to Jerusalem bringing eight slaves. He entered Jerusalem and however much he looked he could not find a house to rent. He came to the monastery of the Ethiopians and he said to the monks, ‘[Give me] a house, I beg you. I am your brother in faith’. [The Ethiopian monks] said, ‘He is our brother in faith’ and [they] gave him a house. After he entered [the monastery], his slaves started to beat [the Ethiopians]. While they were fighting, he said [to the Ethiopians], ‘Come here’, [then] he intimidated them [and] made them leave.”

Likewise, in the legend of the Trojan Horse, Greeks built a large wooden horse as a peace offering to Troy, a city they failed to conquer.31

The Trojans, believing it a harmless gift of Greek surrender, brought the horse inside their fortified city as a trophy. Then, at night, Greek soldiers hidden within emerged, opened Troy’s gates, and allowed their army to invade, causing the city’s destruction.

The context is wildly different, but the deceptive tactics are more or less similar in the two examples.

Foreign confirmation comes from an 1852 letter by Anglican Bishop Samuel Gobat.32

He wrote that the Ethiopians were

“both intelligent and respectable, yet they were treated like slaves, or rather like beasts by the Copts and the Armenians combined.”

Gobat went on, writing:

“[the Ethiopians] could never enter their own chapel but when it pleased the Armenians to open it.”

On other occasions, Tewahedo Christians were unable to:

“get their chapel opened to perform the funeral service for one of their members.”

And:

“The key to their convent being in the hands of their oppressors, they were locked up in their convent in the evening until it pleased their Coptic jailer to open it in the morning, so that in any severe attacks of illness, which are frequent there, they had no means of going out to call a physician.”

The significance of these revelations cannot be understated, and here’s why:

According to Gobat,

“When the Ethiopians were in Jerusalem, they suffered from abscesses and perished.”

In other words, in the mid-19th century, Christians of Jerusalem deliberately and maliciously exposed Ethiopians to disease, barring them from receiving medical attention and directly contributing to the near annihilation of their religious community.

This is not only unjust. This is not only cruel. This act is un-Christian.

When Anglican missionary William Jowett visited Dayr al-Sultan in 1823, he recorded that there were some 20 Ethiopians living in it.33

He also mentions that those Ethiopians had a library from which he bought the Ethiopian New Testament in two volumes.

Gobat attests to the existence of these books and other records, writing in his letter:

“I myself saw the books stored together with the documents 25 years ago.”34

This, when he visited Jerusalem for a first time in 1826.

Per Welde Medhen:

“But later when death finished them off, the Egyptians took possession of it. They left their [own] monastery and entered the Ethiopian monastery. They said, ‘It is the property of our children. It should belong to us’ [and] they burnt 81 books which were there. In the books there were archival records. [They burnt the books] to destroy them.”

Russian historian and jurist Boris Emmanuilovich Baron Nolʹde wrote a memorandum about the incident, based on independent research he conducted during his time in Jerusalem.

In it, he confirms the foregoing events.

Beyond infecting Ethiopians with disease and destroying their records, Welde Medhen describes how the Copts looted Ethiopian possessions from several of their chapels:

“[they] took sacred vessels: a paten, a chalice, a large paten, a spoon [and] an asterisk of [the sanctuary of] Golgotha; a paten, a chalice, a large paten, a spoon [and] an asterisk of the [sanctuary of] Calvary; a paten, a chalice, a large paten, a spoon [and] an asterisk of the [sanctuary of the] Cross, [and] twelve silver censers; the patens and the chalices of the three sanctuaries were golden…”

Any Ethiopian monks who survived this religious, and perhaps even ethnic, cleansing were not spared either.

In the 1830s:

“A priest called abuna Girgis…entered Dayr al-Sultan…He cut out [a part] from the place [of Ethiopians] and sold [it] to the Russians for 700 [coins of] gold…”

In the 1840s:

“After abuna Girgis came abuna Basiliyus. He, in turn, expelled completely all the [Ethiopian] monks from their monastery…they departed weeping. Although they complained to the judge, he did not listen to them.”

What is especially interesting about Welde Medhen’s account is that it is consistent with the accounts of those foreigners before him.

In fact, the most important claims he makes were made in two volumes of a book published by Greek historian Benjamin Ioannidès in 1867 and 1877, respectively.35

To paraphrase another scholar’s reading:

“At first, the Ethiopians and the Greeks shared the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but the Ethiopians lost two thirds of what they possessed to the Greeks, the Westerners and the Armenians. The remaining one-third, Dayr al-Sultan, was then taken over by the Copts, who took advantage of the deaths of the Ethiopian monks. The Copts then had the Ethiopians’ belongings burnt.”36

Dayr al-Sultan has been known to Ethiopian and other Christians as “Dary al-Sultan” since the time of Saladin.

However, after Copts began to occupy it illegally, Welde Median reveals:

“They [the Egyptians] changed the name [of the monastery] and called it ‘monastery of Egypt’, and wrote it [on a sign], whereas it was called Dayr al-Sultan. But no one accepted it. Rome (in reference to Greeks, heirs of Eastern Rome) said [to the Egyptians], ‘You are not allowed to hang the sign in a place that does not belong to you’. And so the Egyptians took [it] down because it was not their place.”37

Although Copts accuse Ethiopians of collaborating with Israeli officials to change the locks of the monastery doors on Easter Sunday (March 29) in 1970, Copts did exactly that almost a century before.

Welde Medhen’s account above is one proof, but we have additional confirmation from Giovanni Battista Albengo, who wrote in 1893 that:

“Arif, pasha’s secretary, assisted by the Egyptian metropolitan Basiliyus, by two monks from the Armenian monastery… broke the door of the chapel, made another key and gave it to the Egyptian bishop.”38

In 1971, the Supreme Court of Israel ordered that Dayr al-Sultan be “returned” to Copts, but this decision has never been enforced, for obvious reasons.

While this is welcome, Ethiopians still do not possess their historic chapels, and even their access to them is severely limited, as you can see below.

Closing words

Ultimately, all Christians, regardless of background, deserve the right to worship wherever they please—including in Dayr al-Sultan.

However, denying Ethiopians’ historic ownership and preservation of their monasteries, their chapels, and their libraries is a slight to the truth—and to God.

Thanks for reading! If you appreciate my work, consider supporting me at any of the links below. Until next time,

-EM

Cited in Enrico Cerulli (1943), “Etiopi in Palestina,” vol. 1, pp. 1-2.

As cited in George Hatke, “Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa,” section 3.3.2.

Ibid.

Cosmas Indicopleustes (c. 525 AD), “The Christian Topography,” book 11, tr. J. W. McCrindle (1897), p. 335.

Marilyn Heldman (1992), “Architectural Symbolism, Sacred Geography and the Ethiopian Church,” Journal of Religion in Africa 22, no. 3, p. 227.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 226.

Ibid., p. 228.

“The Book of the Saints of the Ethiopian Church: A Translation of the Ethiopic Synaxarium (Mashafa Senkesar): Translated from manuscripts Oriental 660 and 661 in the British Museum,” p. 914.

Heldman, “Architectural Symbolism,” p. 226.

Ibid., p. 228.

Ibid.

Abba Philippos, “The Rights of the Abyssinian Church in the Holy Places, Documentary Authorities,” vol. 1.

Archbishop Basilios (1991), “Jerusalem, Coptic See Of,” In The Coptic Encyclopedia, vol. 4, edited by Aziz Suryal Atiya, 1324a–1329b. New York: Macmillan, 1991.

Denys Pringle, “The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem,” p. 497.

Otto Meinardus (1965), “The Ethiopians in Jerusalem,” p. 117.

Archbishop Basilios, “Jerusalem, Coptic See Of.”

Paul and Janet Starkey, “Pious Pilgrims, Discerning Travellers, Curious Tourists: Changing patterns of travel to the Middle East from medieval to modern times,” p. 16

Archbishop Basilios (1991), “Dayr Al-Sultan,” In The Coptic Encyclopedia, vol. 3, edited by Aziz Suryal Atiya, 872b–875a. New York: Macmillan, 1991.

Archbishop Basilios, “Jerusalem.”

Tigab Bezie (2013), “The Ethiopian Religious Community and Its Ancient Monastery, Dier es Sultan in Jerusalem from Foundation to 1850s,” Journal of Ethiopian Church Studies, no. 3, p. 58.

Archbishop Basilios, “Dayr Al-Sultan.”

Oded Peri (2001), “Christianity under Islam in Jerusalem: The Question of the Holy Sites in Early Ottoman Times,” p. 24.

Amnon Cohen and Bernard Lewis (1978), “Population and Revenue in the Towns of Palestine in the Sixteenth Century,” p. 91.

Kirsten Pedersen (1996), “The Ethiopian Church and Its Community in Jerusalem,” p. 34.

Ibid., p.124.

Cohen and Lewis, “Population and Revenue,” p. 86.

Madain Project, “Deir as Sultan.” https://madainproject.com/deir_as_sultan

Cited in Pedersen, “The Ethiopians,” p. 26.

Kate Matthams Spencer (2021), trans., “Amharic Text of Walda Madhen and English Translation,” in The Monk on the Roof , pp. 239–267.

As told in Homer’s Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid.

Ibid.

Cited in Meinardus, "The Ethiopians," vol. 3, рр. 129-131.

Spencer, “Amharic Text,” p. 245.

BENIAM IΩΑΝΝΙΔΟΥ (1877), “ΑΓΙΑ ΠΟΛΙΣ ΙΕΡΟΥΣΑΛΗΜ ΚΑΙ ΤΑ ΠΕΡΙΧΩΡΑ ΑΥΤΗΣ”

In “The Monk on the Roof,” pp. 64-74.

Spencer, “Amharic Text.”

Ibid.