It was the 10th century AD—Aksum just collapsed, its ruling class migrated south to the Amhara region, and behind them was a huge power vacuum.1

Who filled it—and how—is the topic of this week’s article.

Ethiopian sources unanimously agree that the Zagwe Dynasty (960-1270) was primarily composed of Cushitic-speaking Agew people. They are likely Ethiopia’s oldest indigenous community.

The name ዛጔ (“zagwe”) is a corruption of a much older term, Ath-agaou (or Ath-agew), which is attested in Aksumite inscriptions from the 3rd century AD.2

While both refer to the Agew ethnic group, the former means “of Agew” in Ge’ez, and the latter is said to mean “sons of Agew,” though the language is uncertain.

The first Zagwe ruler, Mara Teklehaimanot, took the throne c. 960 AD.3 This came after the Solomonic rulers of Aksum were deposed by a rebellious, pagan woman from the kingdom’s southwest.4

Traditionally, she is known as “Queen Yodit” and tends to be associated with Judaism due to her destruction of churches and persecution of Christians.

In the chaos that followed, Muslims (and pagans) came to occupy most of Ethiopia’s historical territories, or at least project their influence there.

One of the greatest consequences of this was the loss of the ancient port city of Adulis.

It served as the empire’s foremost sea outlet since its conquest in the 1st century AD.5

The revenue gained from the trade that took place in Adulis was equally lost, and Ethiopia was without doubt weakened by it.

Beyond the coastal areas, Muslims also took control of large swaths of land in the “Christian” highlands of Tigray and Eritrea.

Specific families that crossed the Red Sea from Yemen left behind multiple Kufic Arabic inscriptions that support their presence.

The one on the left, found in Kwiha of Eastern Tigray, dates to the early 11th century and belonged to the Yamami Family. The right is on a group of islands claimed by Eritrea and was inscribed in the same century.

Around this time, Egypt was ruled by Fatimids, who likely supported the settlement of Arabs and Arabized groups in Ethiopia.6

Nevertheless, once there, the Muslims did not stay for long.

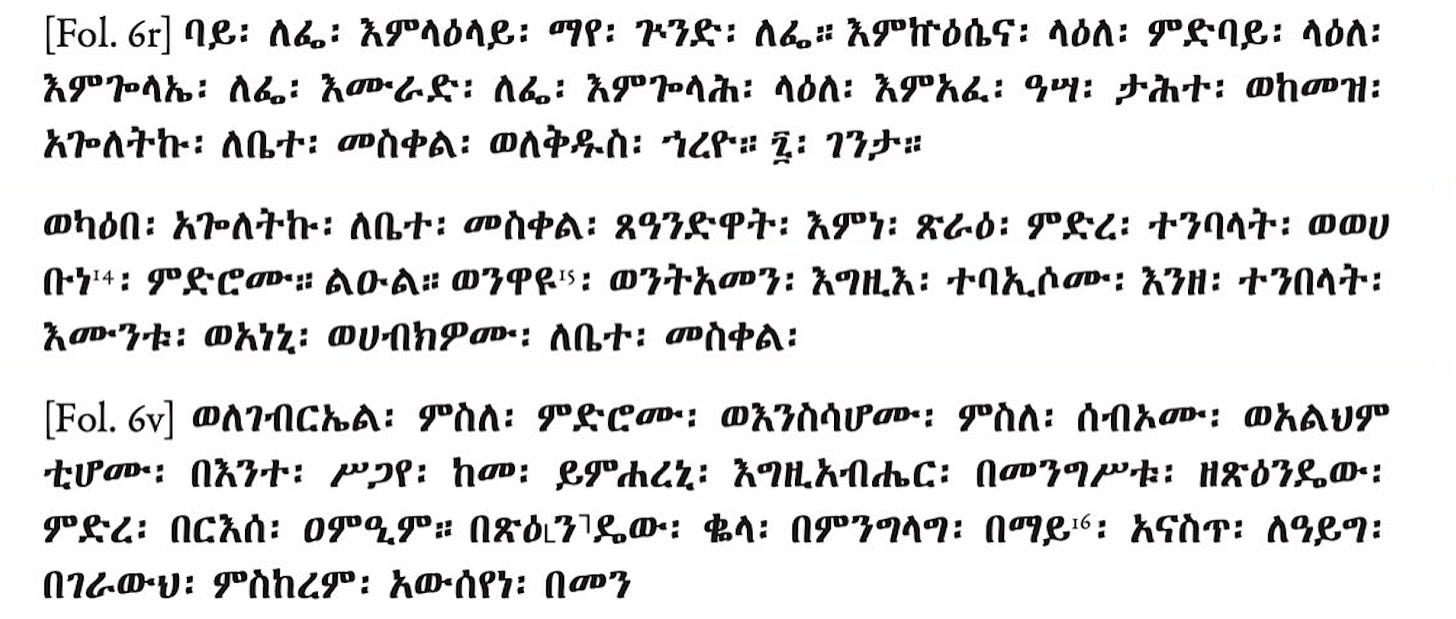

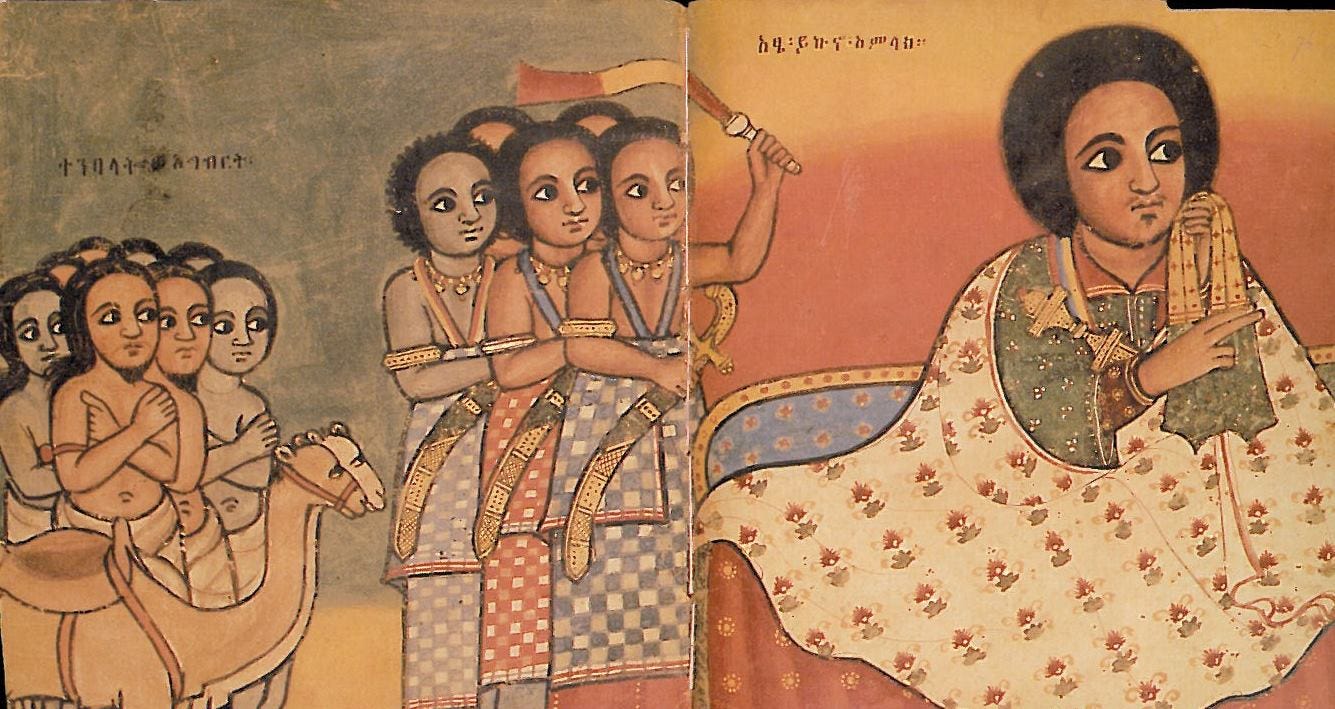

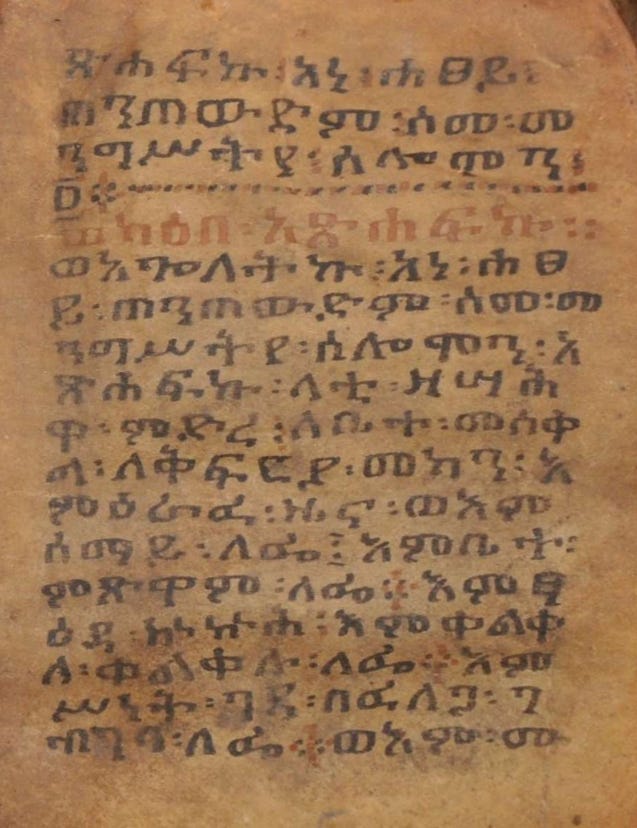

A late 11th to early 12th century royal chronicle attributed to King Tentawdem confirms that the Zagwes waged war on the settlers and successfully expelled them.

This is one of the very few Ge’ez manuscripts produced during the Zagwe era.

Although some have suggested the Zagwes were Tigrinya-speakers, evidence for this claim is severely lacking. On the contrary, Zagwe literature exhibits clear Amharic influences—as seen in words like አጽሐፍኩ (ʾäs'əhäfəku), or “I wrote.”

Firstly, a Tigrinya-speaker would have used the letter ኣ (ʾa) instead of አ (ʾä). Secondly, the ending ኩ “ku” does not apply to the past tense for the first-person in Tigrinya. It is used in Amharic and G’ez only. Finally, the root verb ጽሐፍ (s'əhäf), meaning “to write,” is also unique to Amharic and Ge’ez.

We can be confident in this assertion since ጽሐፍ does not exist in the Tigre language, which was once identical to Tigrinya, just like the ethnic groups that speak these languages.

To date, the word for “to write” in Tigre is ከትበ (kätəbä), an Arabic loanword. Thus, መጽሐፍ (mäs'əhäf) and other variants of the term must have been borrowed into Tigrinya from Amharic.

The Amharic influence on Zagwe literature is unsurprising, given that the capital of these monarchs was in Lasta and other parts of the Amhara region.7

Now, despite their actions against Muslims, the Zagwes generally had good relations with the Fatimid caliphs of Egypt.

Evidence of this comes from the Church of Abreha weAtsbeha in Eastern Tigray.

It was built by Agew rulers in the 11th century, immediately following their Crusades in the area.8

In it are a number of impressive architectural features present in earlier Ethiopian churches.

However, certain designs are new and may indeed be foreign, such as the geometric pattern below.

The same “swastika-like” pattern is visible on another Church built by the Zagwes, specifically Emperor Lalibela (c. 1181-1221).

This one below is called Bete Mariam and is found in the Amhara region.

It was carved out of a mountain by Amhara architects, who supported the king’s rise to power and were rewarded for it with key positions in government.9

The pattern even appears on a 10th-11th century Church in Eritrea, called “Aramo.”

It is found in Akkele Guzay, another area under Zagwe control.

Thus, the construction of this Church may be attributed to the Agews as well.

In fact, the Zagwe Dynasty dominated most of the Tigrayan and Eritrean highlands, despite having their capital elsewhere.

Since the earliest days of their reign, they had the power to choose the rulers of Ethiopia’s coastal region, the northern part of which is colloquially called ምድረ ባሕር (mədərä bahər ), or “Land of the Sea.”

Its ruler was a vassal with the title ባሕር ነጋሢ (bahər nägaśi), or “Ruler of the Sea.” Today, the Amharic term ባሕር ነጋሽ (bahər nägaš) is most widely used, though the position was virtually dissolved in the late 16th century.

The Zagwes also hand-picked other rulers of other Ethiopian regions, such as Agame in Tigray, and Bur, which covered much of the Eritrean highlands.

Scholars agree that the geometric designs under analysis found their way to Ethiopia through textiles exported to Egypt from India and later sent to Ethiopia as gifts.10

But what was the nature of these “gifts”? Interestingly—tribute!

Indeed there are early 13th century writers that confirm the Egyptian sultans had a tradition of paying tribute to Ethiopia, such as in the Fatimid era.

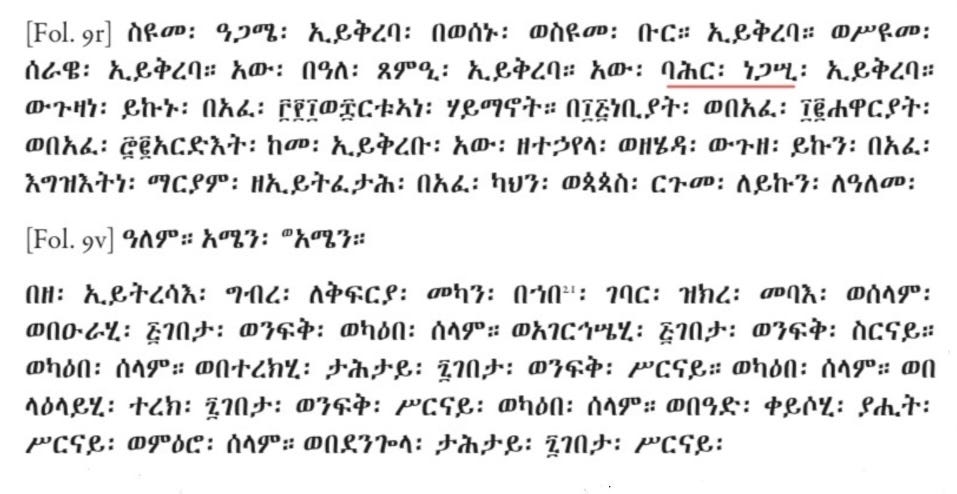

Even more interesting is that after the Ayyubids succeeded the Fatimids in 1171, they stopped paying tribute—and as soon as they did, God struck all of Egypt with famine and drought, leaving them no choice but to pay their dues to Ethiopia.

Let’s put that into perspective. The map below shows the territories conquered by the Ayyubids. Now compare that to the size of Ethiopia between the 10th and 13th centuries from the first map above.

Yes, it really happened!

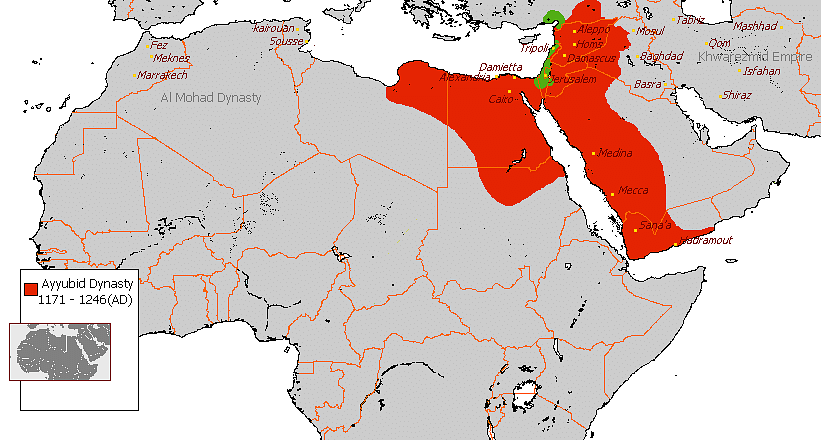

Due to their positive relations with the Egyptians, communities of Ethiopian Christians could make safe pilgrimages to monasteries in Egypt, Israel, and beyond.11

One place they visited was the Dayr-al-Suryan monastery in Egypt, established by Syrians in the 6th century.

There, they collaborated with Coptic, Armenian, Syrian, and other Christians to produce religious texts in multiple languages.

As usual, the Ge’ez text on the far left exhibits multiple Amharic influences, including those already described. Hence, it was most definitely produced by Amhara monks.

Around this time, Atlantic Europeans took an interest in Ethiopia. What struck their interest was a letter purportedly written by a powerful, though mysterious, Christian ruler from the East.

These Europeans spent several centuries searching for this king, known to them as “Prester John.” This figure was most likely the 12th century Emperor Yemrehana Krestos or one of his predecessors.12

Part of the urge to meet the king stemmed from the European desire to find an ally with whom they could defeat the Muslims who occupied Jerusalem.

The search brought them to the Middle East, South Asia, and even Central Asia, until the Portuguese finally reached Ethiopia in the late 15th century and found their “Prester John.”

One could make the argument that this event led to European colonialism itself.

Unlike Tigray and Eritrea in the north, other Ethiopian provinces, particularly Shewa, were entirely independent of the Zagwes.

There, small communities of Christian Amharas, direct descendants of the Aksumites, survived on their own for centuries despite being surrounded by pagans and Muslims.13

It was from his birthplace of Bete Amhara and his stronghold of Shewa that the Amhara Emperor Yekuno Amlak—himself descended from the last king of Aksum, Dil Naod—restored to the throne the Solomonic Dynasty. In this, he was aided by the Amhara Saints Tekle Haimanot and perhaps also Iyesus Krestos Moa.14

This, contrary to popular myth, was a peaceful exchange of power that marked the end of Agew rule once and for all.15

Thanks for reading! If you appreciate my work, consider supporting me at any of the links below. Until next time,

-EM

Butzer, Karl. (1981). “Rise and Fall of Axum, Ethiopia: A Geo-Archaeological Interpretation,” p. 492.

Munro-Hay, Stuart. (1991). “Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity,”pp. 186-187.

Dillmann, August. (1853). “Zur Geschichte des abyssinischen Reichs.” in Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. Vol 7, pp. 338–364.

Munro-Hay, op.cit., p. 94.

“The Periplus Maris Erythraei,” pp. 50-52. Ed. Lionel Casson.

Muehlbauer, Mikael. (2023). “Bastions of The Cross. Medieval Rock-Cut Cruciform Churches of Tigray, Ethiopia,” p. 53.

Doresse, Jean. (1917). “Ethiopia: Ancient Cities and Temples,” p. 93. Tr. Elsa Coult.

Muehlbauer, op.cit., p. 133.

Hable Selassie, Sergew. (1972). “Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History: 1270-1527,” p. 265.

Muehlbauer, op.cit., p. 178.

Abir, Mordechai. (1980). “Ethiopia and the Red Sea,” p. 15.

Derat, M.L. (2012). “King and priest and Prester John: analysis of the Life of a 12th century Ethiopian king, Yemrehanna Krestos.”

Gebremariam, Taye. (1922). “History of the Ethiopian People,” p. 18.

American University. (1971). “Area Handbook for Ethiopia,” p. 209. Foreign Areas Studies Division.

Mekuria, Tekle Tsadiq. (1935). “The History of Ethiopia.”