Intro

Zara Yaqob (Amharic, Ge’ez: ዘርአ ያዕቆብ) was born c. 1399 AD in the former province of Fetegar, central Ethiopia.

Some 1,100 years prior, Flavius Valerius Constantinus was born in Niš, a city in southern Serbia.

Both would eventually take on the throne name Constantine / ቈስጠንጢኖስ and leave a lasting mark on world history.

This article explores their respective reigns.

Rise to power

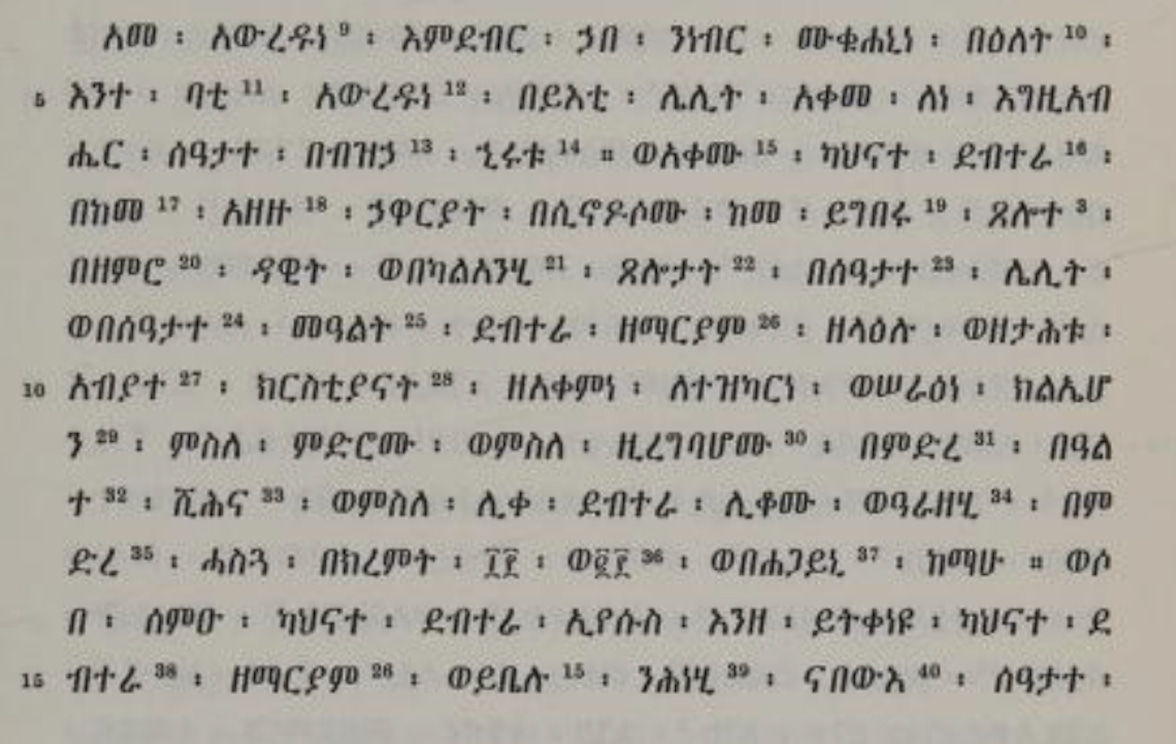

The Ethiopian Constantine’s royal chronicle was written in Ge’ez by Amhara scribes shortly after his death.

It states that Zara Yaqob’s father was the Amhara Emperor Dawit I (1382-1413). His mother was Egzie Kebra, another Amhara royal.1

The Byzantine Constantine, meanwhile, was born to a Greek mother and Roman father.2

Both came to power in a time of religious controversy and political upheaval.

After their father died in 1413, the eldest sons of Emperor Dawit took the throne one after the other. As the youngest male heir, Zara Yaqob was viewed as both a threat and a liability to his siblings.

According to the emperor’s own book, he was confined (most probably by his brothers) atop the infamous mountain prison for princes, known as Amba Gishen, for roughly 20 years. This was done in relative solitude, and Zara Yaqob missed out on much of the political and military education enjoyed by his predecessors.

On the other hand, Constantine I travelled from place to place, spending most of his youth surrounded by other nobles and their advisors. This gave him early exposure to the persecution of Christian minorities by the pagan ruling class of the day.

Around year 306, Constantine I's own father died in York, Britain. The occupying Roman army immediately proclaimed him as Augustus (senior emperor), bypassing the traditional Tetrarchy system that required approval from the other ruling emperors.

In 1436, just two years after his confinement concluded, Zara Yaqob was also made emperor. His chronicler describes the majestic coronation thusly:

Legal and economic policies

Leading up to his coronation, Emperor Zara Yaqob reorganized the administrational structure of all his provinces.

The chronicle states that he made his own daughters, a niece, and several of his sisters rulers over these domains. In Tigray he appointed Bahr Mengesha; in Damot, Medhen Zemada; in Ifat, Amde Giyorgis, and so on.3

The emperor also hand-picked the ruler of today’s Eritrean highlands, where a vassal kingdom colloquially called “Medre Bahr (‘Land of the Sea’)” once stood.

Its ruler was referred to as the “Bahr Negash (‘Ruler of the Sea’),” a position first attested in the 11-12th century Ge’ez chronicle of the Agew King Tentawdem of the Zagwe Dynasty, who also had the power to appoint him.4

Emperor Zara Yaqob extended this vassal ruler’s jurisdiction, granting him control over new lands, including Shire, Seraye, Hamasen, Bur, and others.

Later on he would establish military colonies in many of these territories. A 15th century manuscript explains that when a group of elite archers from Shewa of the Amhara region settled in the Eritrean plateau, 5

“the earth trembled… and those who inhabit (the earth) were distressed.... All the local people left the country and fled out of fear.”

Emperor Constantine I made his fair share of reforms, too.

This included reorganizing the currency system through the introduction of the gold solidus, which helped stabilize inflation. He also reformed the army, adding mobile units (comitatenses) to respond more effectively to invasions and civil conflicts.

He gave his people public baths, established military posts, and built infrastructure, including the Walls of Constantinople and the Great Palace.

Likewise, after defeating the Garad (“ruler”) of the powerful Muslim Sultanate of Hadiya, Emperor Zara Yaqob captured Sultan Mehmed's daughter, Princess Eleni, baptizing and making her his wife.6

To thank God for his victory, the emperor went to the land of Tsehay (“Sun”) in Amhara, climbed atop a beautiful mountain, and built two churches—Mekane Gol and Debre Negwedgwad.7

But that’s not all. Emperor Zara Yaqob also ordered the construction of a stunning palace at Debre Iba. According to the chronicle, it:8

Measured 30 feet in height;

Was “white like ‘snow’” (በረድ);

Featured an Arc de Triomphe;

Had a separate house for pet lions;

Was enclosed by a 10-foot-tall gate;

And was surmounted by a golden Cross.

Thus, a digital reconstruction of the castle would look something like the following:

Some 400 years later, the British military officer William Cornwallis Harris visited Ethiopia. While travelling across Shewa, he stumbled upon what he believed were the ruins of Emperor Zara Yaqob’s ancient palace.

Although his description naturally failed to do it justice, it was not too unlike the one above.9

Crusades

In 1441, the emperor received news from the Patriarch of Alexandria, Yohannes XI, that Egyptian Muslims had “destroyed the monastery of Metmaq.” This was done out of anger, for the Holy Virgin Mary had just appeared at the locality, inducing thousands of Muslims to convert to Christianity after witnessing the miracle.10

Right away, Emperor Zara Yaqob ordered the construction of a Church by the name of Metmaq and dedicated it to Mary.

Afterward, he dispatched a letter to the Egyptian sultan, warning him of dire consequences if he did not correct his ways and desist from attacking Christians. Notably, the emperor threatened to divert the course of the Nile River itself.11

He also demanded that the destroyed Churches be rebuilt. Along with this letter he sent a batch of expensive gifts as an incentive, including a multitude of weapons made entirely of gold.

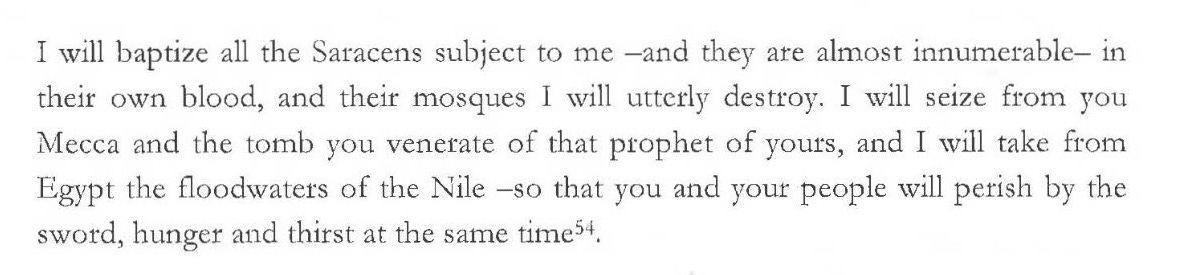

A translation of the original letter, written by one of the emperor’s diplomats in Arabic, is below.

Two years later, the sultan was still unobliging.

So, Emperor Zara Yaqob wrote once more—this time with a much sterner tone.

Part of the reason why the Adalite problem persisted for so long was Zara Yaqob’s concern for what might be done to innocent Coptics in Egypt if he, in retaliation, harmed the Muslims in his own territory.

But in 1445, he decided he would end Adal for good.

The chronicle states the following:12

“Zara Yaqob thereupon ordered his men to raise the royal umbrellas, blow the trumpets and beat the drums; at the same time he commanded the standard-bearers to begin the advance on the enemy. 'Everyone, we are told, 'was impressed by this imposing and majestic spectacle. Arwe Badlay in particular was ‘perplexed and seized with fear’ as he had been led to believe that the attacking force was commanded not by the Emperor but by a minor chief.”

The emperor promptly charged at the enemy, crushing infidels with his horse and making his way to the sultan, Arwe Badlay, whom he piereced with his lance. The infidel’s head was later removed and his body cut to little pieces, which were distributed to all the holy places of Ethiopia.13

The deceased sultan’s army immediately took flight but still could not escape the slaughter. The chronicle continues: “not one soldier survived out of the army of the enemy.”14

Together, the threats to divert the Nile and to convert Ethiopia’s Muslim population to Christianity were very effective at scaring the Egyptians into acquiescence. The Mamluk rulers of Egypt not only ended their persecution of Coptics, but Sultan Sayf-ad-Din Jaqmaq even ended his support for Muslim rebels in Ethiopia, such as the successor of Arwe, named Mohammed Badlay, urging them to submit to the Ethiopian King.15

Emperor Constantine I led a number of his own crusdaes.

In year 312, his army confronted that of Maxentius’ for control over the Eastern Roman Empire, culminating in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. According to tradition, Constantine led his people under Christian banners and uttered the phrase “In hoc signo vinces,” which is Latin for “In this sign (i.e., the Cross), you shall conquer.”

This battle paved the way for the Edict of Milan in year 313, which granted religious tolerance to Christians and set the stage for the Christianization of Rome. Constantine also convened the First Council of Nicaea in year 325 to resolve theological disputes and unify Christian doctrine, which laid the foundation for the Nicene Creed.

Similarly, in 1450 at the Council of Debre Metmeq, Emperor Zara Yaqob ended a centuries-long religious dispute about the Sabbath. The emperor did so by convincing the Coptic bishops to reconcile with the leaders of the Ewostatewosan movement—something that was long overdue.16

City-building

Last but certainly not least, one of Constantine’s most enduring achievements was the founding of Constantinople in year 330. Although it has since been renamed Istanbul and is found in modern-day Türkiye, when it was the Byzantine capital it connected Europe and Asia, serving as a hub for trade, cultural exchange, and more.

Now, contrary to popular belief, Protestantism was not born in 16th century Europe, nor in 17th century North America. Instead, it was born in mid 15th century Ethiopia.

The leader of this heretical movement was “Estifanos,” who hailed from the country’s Tigray region, along with most of his followers.

These Stephanites, like the Protestants who came after them elsewhere, refused to bow to the Cross, refused to honour Mary, and refused to kiss icons of the Virgin Mother and her Child, God. Such is only a mere fraction of their heresies.

Emperor Zara Yaqob gave them many chances to repent. He also invited them to his royal court for a debate. Unable to defend their ideas, the Stephanites became uncivil, cursing the emperor and the Christians of Ethiopia and beyond.

Rightly perceiving their ideology as a national threat, Emperor Zara Yaqob sentenced them to death—by stoning.

Interestingly, the chronicle states that the Roman Catholic, Greek, Egyptian Coptic, and Syrian visitors at the emperor’s court freely selected their own stones and freely partook in the stoning of the heretics. Most of the Stephanite leaders and their senior members were executed on February 2, 1449 (EC).17

Exactly 38 days later, on the Feast Day of the Cross (formerly March 10th, EC) a brilliant light appeared in the Sky above ደብረ ኢባ // Debre Iba, where the judgment was passed. It illuminated the entire night sky, especially above all the Churches in the vicinity. The light shined on the clothes and on the bodies of all the Christians. It looked like a fire, and the Christians could feel the heat of the light, but it did not burn them. This light lasted for several days, and all the Christians were joyous because they got to witness it.18

The Emperor was also pleased, and so from that day forth, the city that was once Debre Iba would be called “Debre Berhan.” This is Amharic and Ge’ez for “The Place of Light.”

It should be noted, however, that the Stephanites did not disappear entirely. Those who were not purged were forced to revert to Tewahedo, or Ethiopian Orthodoxy.

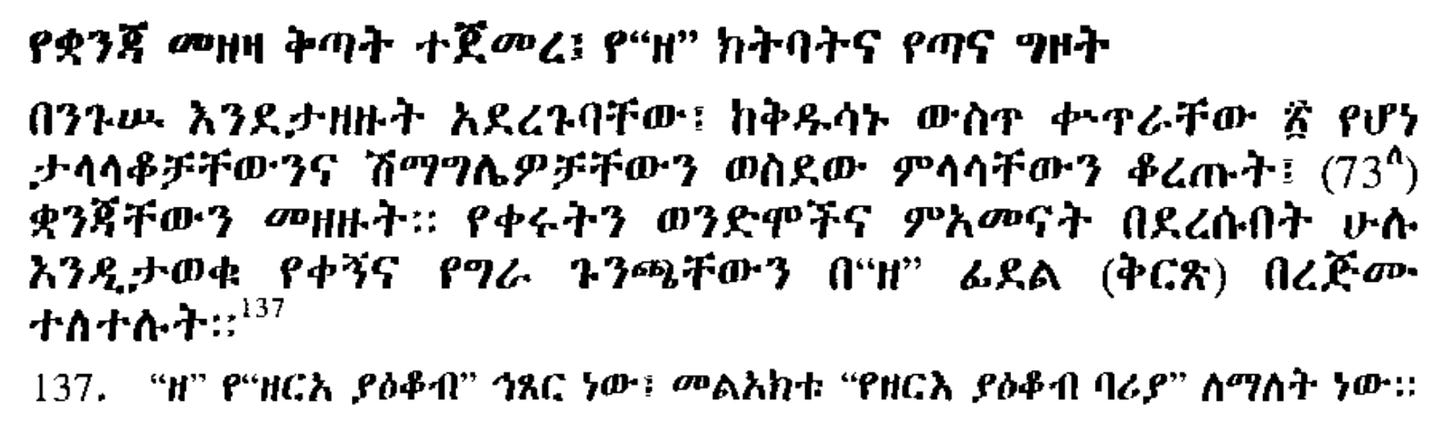

They were also forced to mark their faces with the Amharic and Ge’ez character ዘ (“ze”), representing the first letter of the emperor’s name and signifying that whoever bore that mark was የዘርአ ያዕቆብ ባርያ , or “the slave of Zara Yaqob.”

Nearly 600 years after the emperor’s judgment, many Tigrayans—both young and old—have maintained this tradition and still bear his mark.

Conclusion

So was Emperor Constantine II of Ethiopia really just Emperor Constantine I of Rome reincarnated?

We’ll never really know. All we can be sure about is that both were legendary rulers who reshaped their empires through faith, power, and vision—becoming almost immortal in the process.

Thanks for reading! If you appreciate my work, consider supporting me at any of the links below. Until next time,

-EM

Perruchon, Jules. (1893). “Les Chroniques de Zara Yaqob et de Baeda Maryam,” p. 52, 86.

Kousoulas, D.G. (2003). “The Life and Times of Constantine the Great.”

Pankhurst, Richard. (1967). “The Ethiopian Royal Chronicles,” p. 32.

Derat, Marie-Laure. (2018). “L'énigme d'une dynastie sainte et usurpatrice dans le royaume chrétien d'Ethiopie, XIe-XIIIe siècle.”

Tamrat, Taddesse. (1968). “Church and state in Ethiopia: 1270-1527,” p. 479.

Perruchon, op.cit., p. 59.

Pankhurst, op.cit., p. 35.

Perruchon, op.cit., pp. 23-26.

Harris, W.E. (1844). “The Highlands of Aethiopia.” First London Edition, p. 139.

Pankhurst, op.cit., p. 36.

Krebs, Verena. “Crusading Threats? Ethiopian-Egyptian Relations in the 1440s.”

Pankhurst, op.cit., p. 37.

Perruchon, op.cit., pp. 65-66.

Pankhurst, op.cit., p. 38.

Krebs, op.cit., p. 269.

Tamrat, op.cit., pp. 452-453.

Haile, Getachew. “Deqiqe Estifanos: Behigg Amlak,” pp. 53-54.

Some have identified this light in the sky with what Europeans saw around the same time in 1456 (GC) and what the English call “Halley’s Comet.”