Intro

There is a saying in Ethiopia:

አማርኛ ለገዥዉ፣ ግዕዝ ለጸላዩ፣ ትግርኛ ለድኃዉ።

“Amharic for the powerful, Ge’ez for the prayerful, Tigrinya for the povertyful.”

As offensive as that sounds, it is consistent with history.

Take the German Orientalist Hiob Ludolf, for example. In 1684, he wrote in Latin that Amharic was the royal tongue of Ethiopia, or the ልሳነ ንጉሥ (ləsanä nəguś), and that Tigrinya was the language of commoners, or the ልሳነ ምስኪን (ləsanä məsəkin).

In 1892, Élisée Reclus made similar remarks:

“Of the two chief Abyssinian languages, the Tigriña and the Amhariña, the latter, also derived from Ghez, predominates, thanks to the higher civilisation and political preponderance of the Amhara people. The Amhariña is the language of trade, diplomacy, and literature… Whole libraries of books have been written in this tongue…. The Tigriña dialects possess no literature.”1

More recently, esteemed Tigrayan author Sebhat Gebre Egziabher confirmed a childhood memory from the 1940s.

To translate directly: “Back in Tigray, when a person passed by a wealthy man’s house and the security guard ordered him to stop, the passerby would respond by saying, ‘Sorry, I am poor, I can’t speak Amharic.’”

How the world came to perceive these closely related languages so differently is the topic of this week’s article.

Semitic in general

Based on epigraphy, the oldest known Semitic language in the world is Akkadian, “the language of Assyrians and Babylonians,” first appearing in Mesopotamia nearly 5,000 years ago.

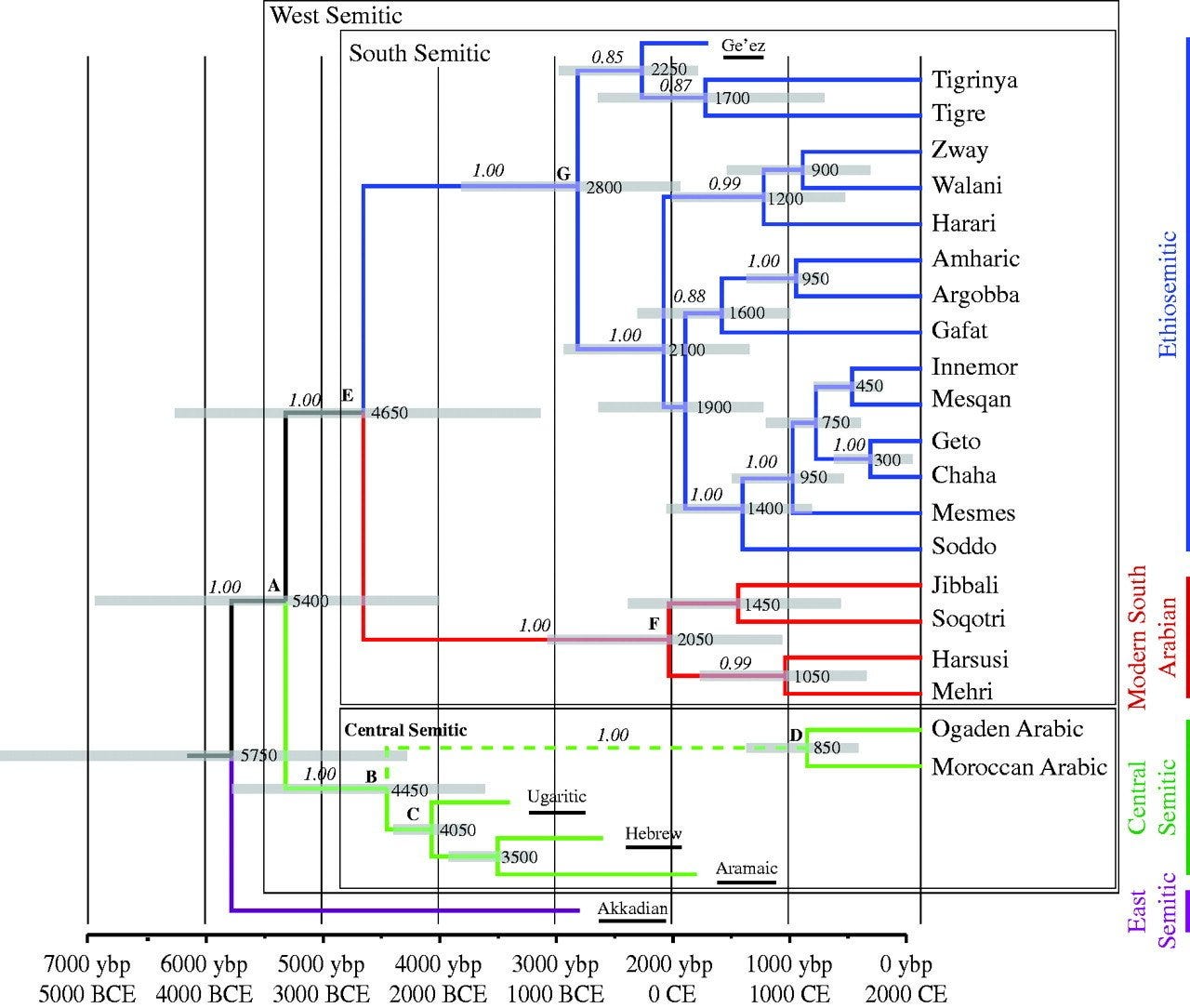

Over in Africa, Semitic languages have been spoken for almost as long. The Ethiopian branch of Semitic speech is believed to have separated from a shared Semitic ancestor some 4,000 years ago.2

In Western scholarship, this language—known locally as ግዕዝ (gəʾəz or Ge’ez)—is often called “Ethiopic.” It falls under the Southern branch of the Semitic language family.

Ethio-Semitic (ES) languages, as the name suggests, are Semitic languages spoken primarily in Ethiopia. There are a dozen or more of these, used in varying ways and to varying degrees, but the most relevant today are Amharic, Ge’ez, and Tigrinya.

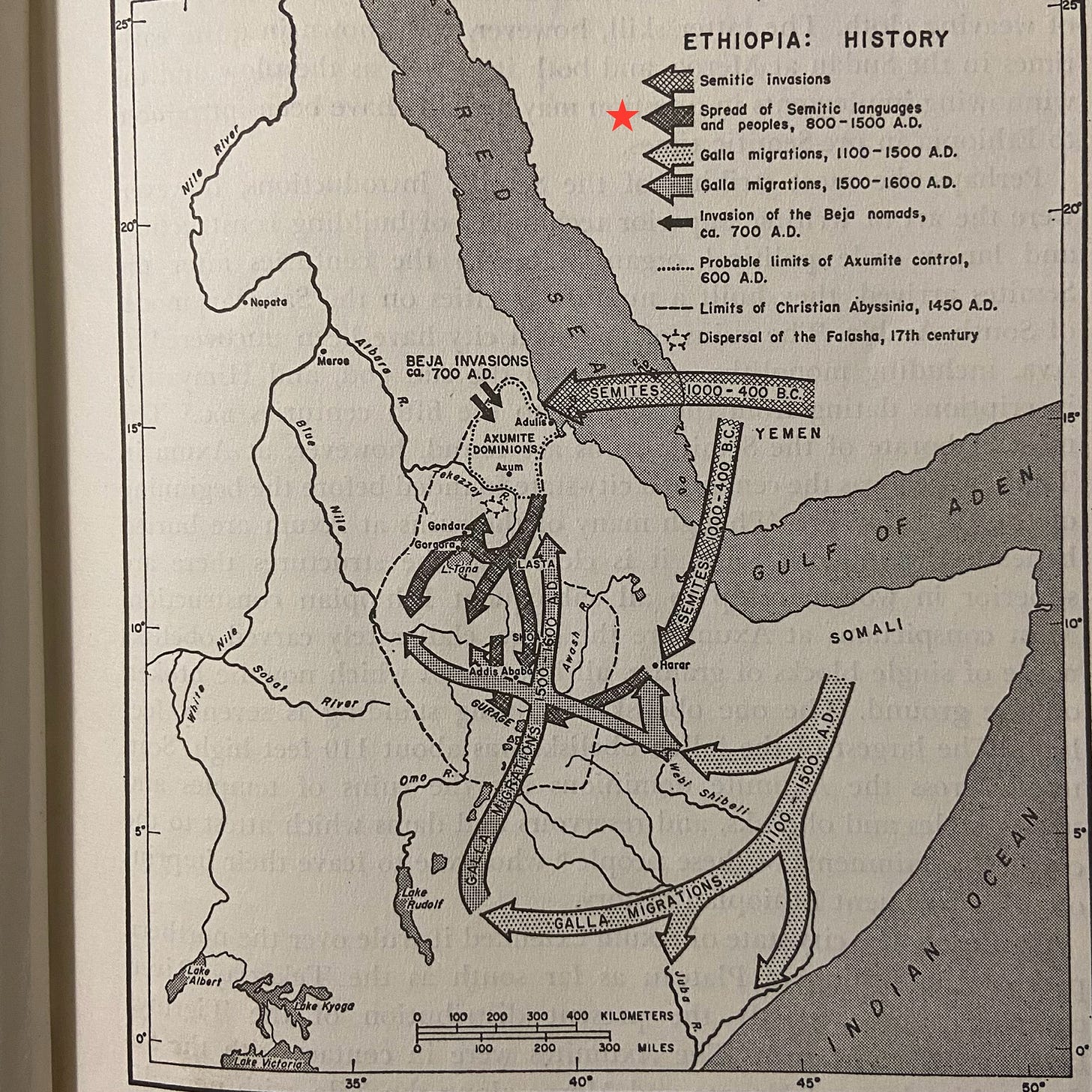

Scholars generally divide these languages into two branches: Northern and Southern (NES and SES). Most agree that speakers of SES descend from “an earlier wave of Semitic immigrants.”3

These people left their homes in the Middle East—mainly the Levant, per genetic studies—and gradually migrated to Ethiopia, the earliest of them arriving some 3,000 years ago.

This explains why, as you will see later, SES languages—namely, Amharic—exhibit the oldest linguistic characteristics in Semitic.

The origins of Ge’ez

Shortly before the Kingdom of Aksum collapsed in the 10th century AD, its ruling class migrated south to the Amhara region.4

Since then, Ge’ez has ceased to be a spoken language, meaning that the Ge’ez of today is no older than 1,000 years.

For this reason, scholars distinguish between the proto-Ge’ez (or “proto-Ethiopic”) spoken by the Aksumites and that which developed into late-Ge’ez (or, for simplicity’s sake, “Ge’ez”) post-Aksum.

Writing-wise, Ge’ez traces its roots to Sabaic, a closely related language used by Ethiopia’s Amhara ruling class from the 11th century BC to the 6th century AD.

For around the same time, Sabaic was also spoken across the Red Sea in South Arabia, where inhabitants of Saba (or “Sheba”), an ancient Ethiopian colony, lived.5

Nevertheless, some of the period’s most important political terms—like the tribe of Ethiopia’s Amhara ruling class, Agazi—originate from and are unique to Ge’ez.

The term is attested on a nearly 2,800-year-old Sabaic-inscribed incense burner from Northern Ethiopia as 𐩺𐩴𐩹 (unvocalized: yägäzä), the Ge’ez equivalent being አግዓዚ (vocalized: ʾägəʾazi).

As Ge’ez only replaced Sabaic as the dominant language around the 1st century AD, the former evolved in the image of the latter.

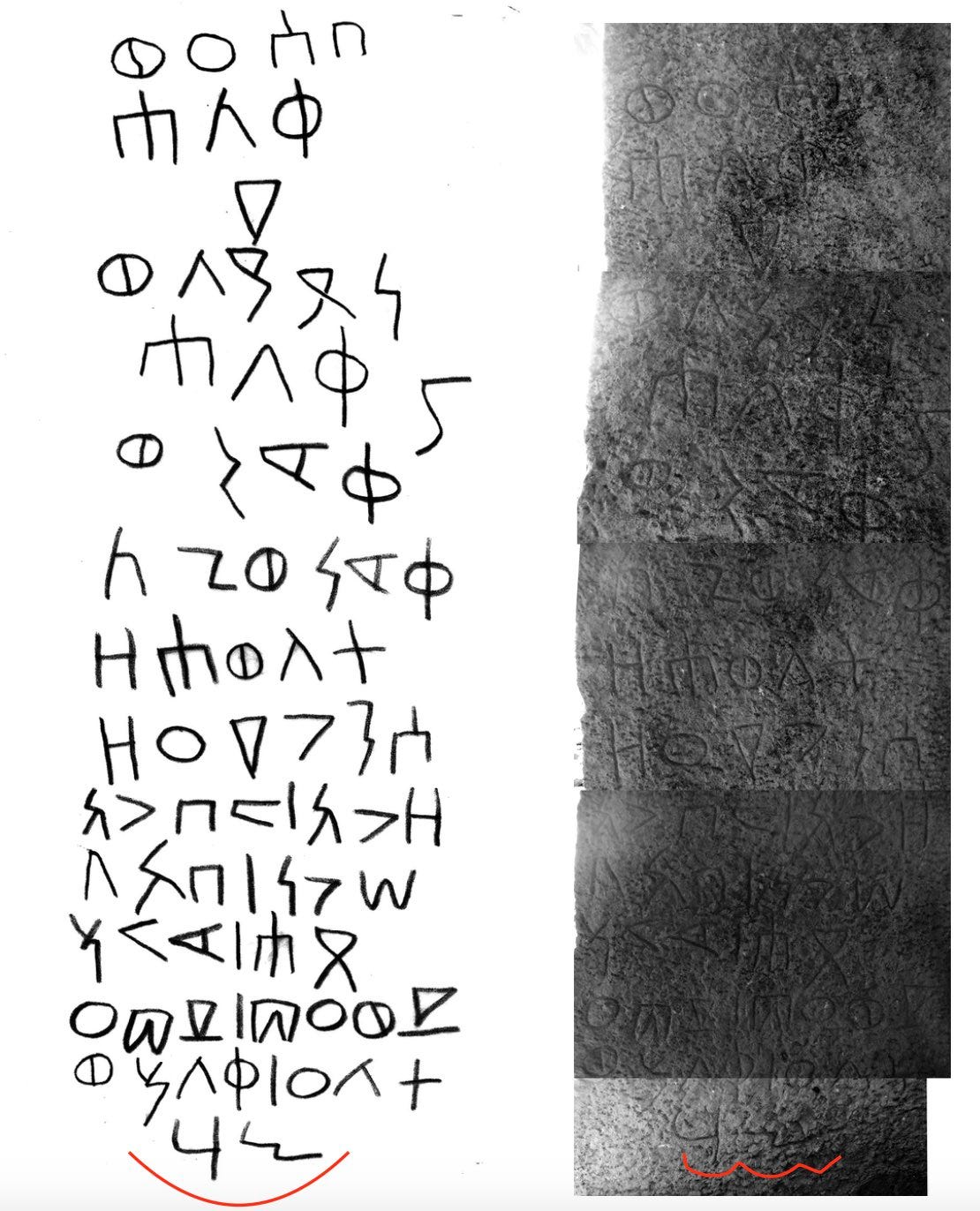

The table below compares the two scripts. Notice how there are only 24 Sabaic letters, which Ge’ez inherited along with the sounds they make when spoken.

A consequence of this is that the ሽ (š) sound, as seen in words like ነጋሽ (nägaš ; Amharic: “ruler”), did not exist in Aksumite or pre-Aksumite times. Indeed, the Ge’ez equivalent of ነጋሽ is ነጋሢ (nägaśi), attested in the 12th century chronicle of the Agew King Tentawdem.

But with Greek influence beginning roughly two millennia ago, Ge’ez adopted two new characters: ጰ (p'ä) and ፐ (pä), and the total became 26 letters.

Before long, another important change was made—vocalization.

This occurred because Christianity demanded the reading of the Holy Gospels, ideally with as few mistakes as possible.

So by the 4th century AD, the Ge’ez script changed from an abjaj, where only consonants were written, to an abugida with written—rather than inferred—vowels.

Almost immediately, 6 variations were added to every letter of Ge’ez, and the alphabet reached 26 x 7, or 182 letters.

Yet the presence of a vocalized letter on the early 4th century coin of King Wazeba, who reigned in the pre-Christian era, weakens the post-Christianity argument for vocalization.

Around this time, the direction in which Ge’ez was read also changed.

Sabaic, like other Semitic languages, was technically read right-to-left. But Ge’ez, for one reason or another, changed the direction from left-to-right.

Number-wise, these first occur in a roughly 1,800-year-old inscription found in Hanzat of the Tigray province.

It was erected by an Aksumite prince named አገዘ (ʾägäzä) in honour of his father, the king, who scored military victories against non-Aksumites in the region.

Scholars like Edward Ullendorff have shown that አገዘ is a word occurring only in Amharic, another indication that Amharas are the only descendants of Aksumites in Ethiopia.6

The number in question is ፶፯ (57), which represents the number of days it took for አገዘ to erect the stele.

In 1922 (GC), renowned Ethiopian historian and linguist Taye Gebremariam identified about a dozen other Amharic names belonging to Aksumite royals, namely, kings.

Among these: አግባ (ʾägəba), አስጐምጉም (ʾäsəguməgum), and ለትም (lätəm).

These names were also identified by the German scholar August Dillmann nearly a century prior. Like Gebremariam, Dillmann cited ancient manuscripts from all corners of northern Ethiopia in which the names were recorded.7

Later developments in Ge’ez

182 characters, up from 24 just a few centuries prior, is a 658% increase.

That’s a lot! But there’s more:

Just like their Aksumite ancestors did in the 4th century, Amharas introduced even more characters into the Ge’ez alphabet, bringing the grand total to over 260.

In fact, Amharas developed the Ge’ez script so much that it became, in effect, the Amharic script, used by all ES speakers today—knowingly or unknowingly.

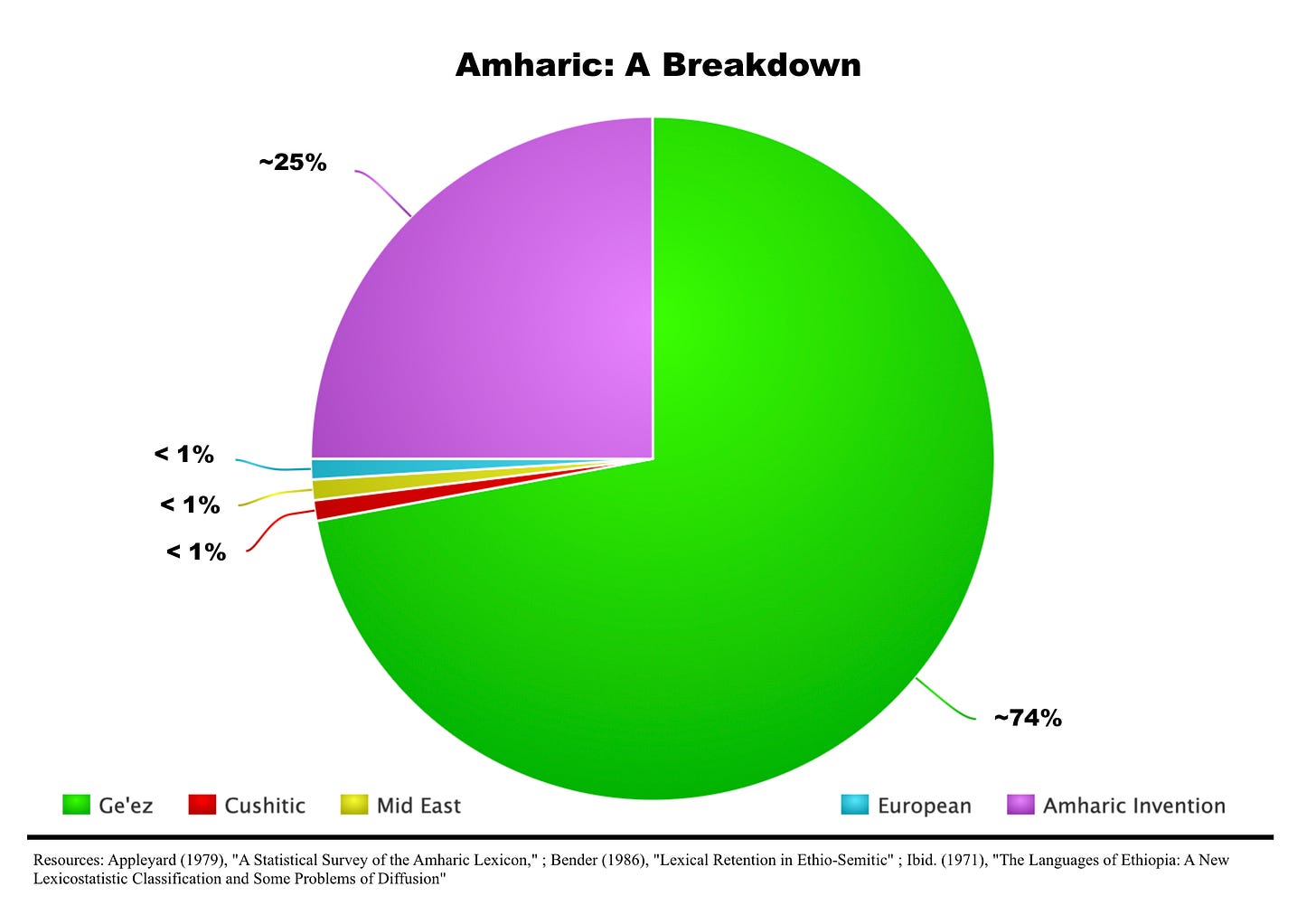

That’s right, some 64 letters used in various ES languages today originate directly from Amharic—roughly 25% of the traditional Ge’ez alphabet.

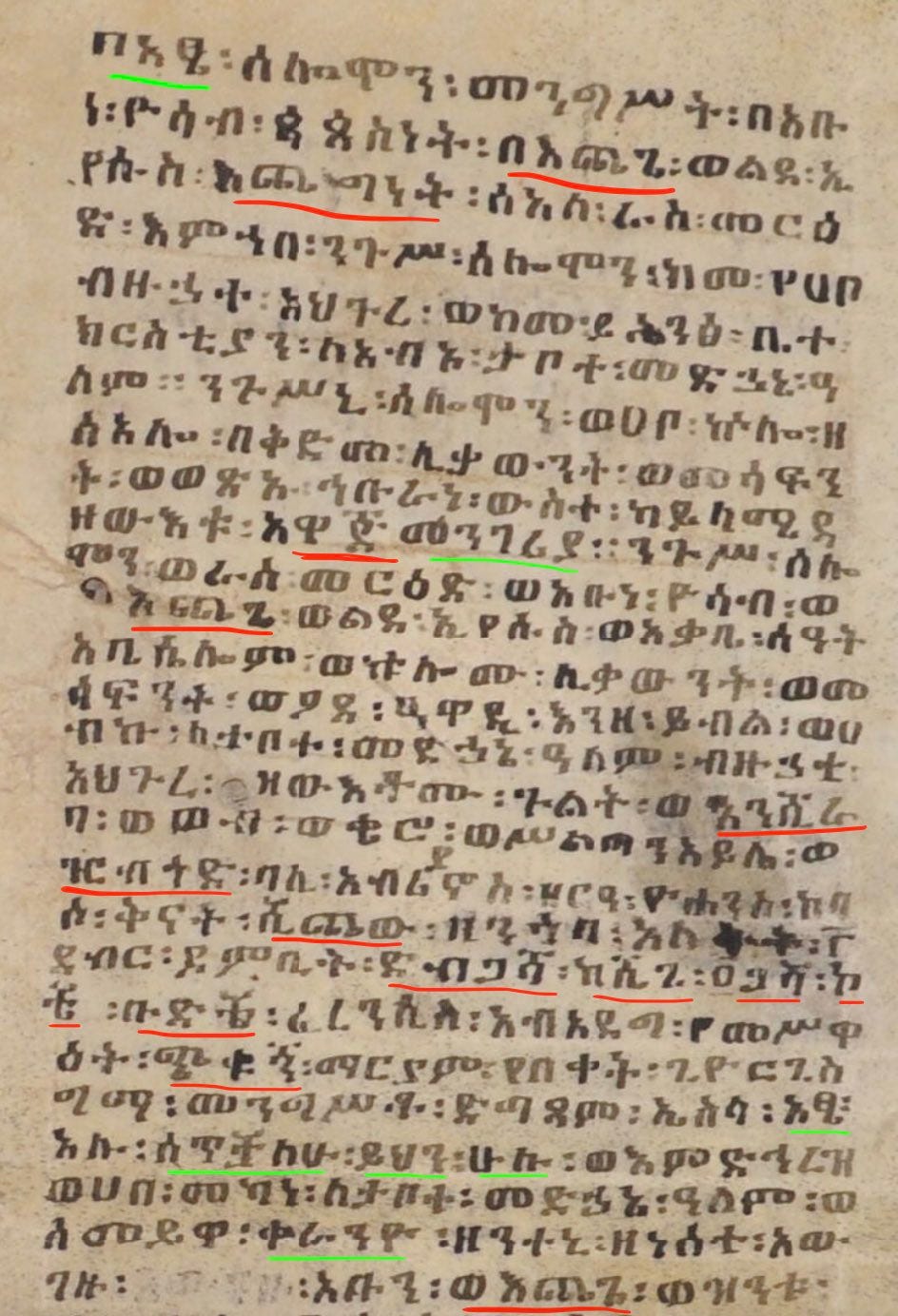

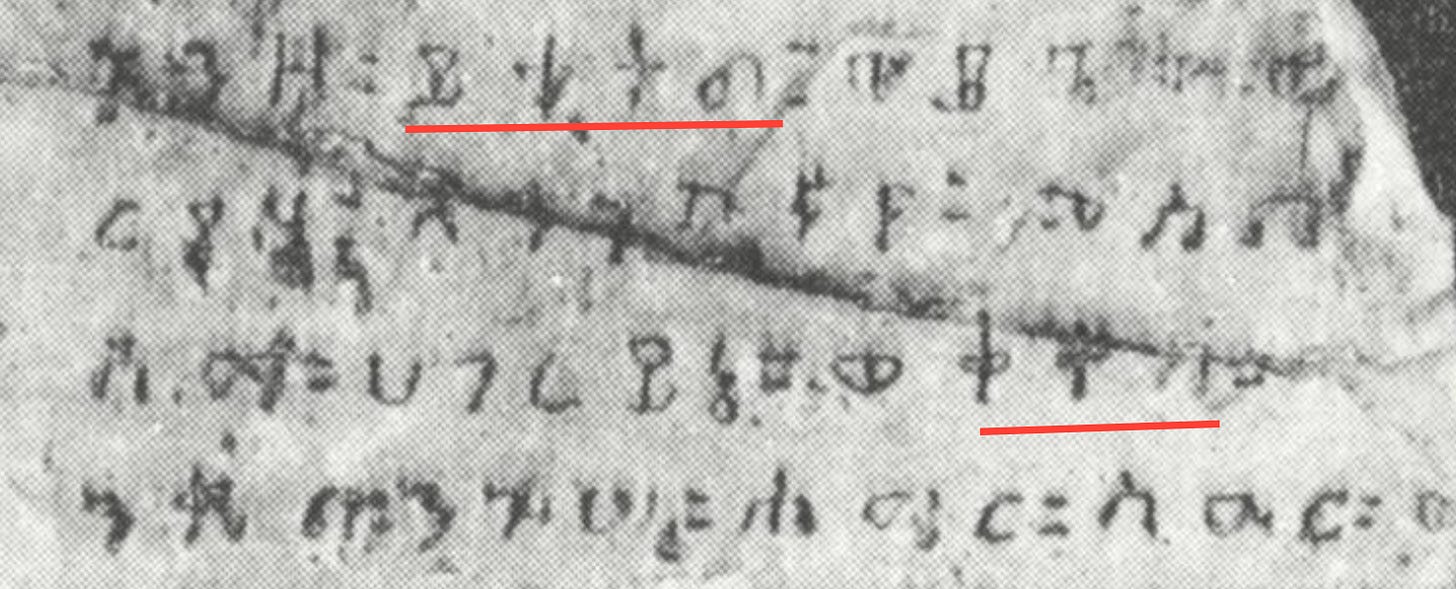

Multiple sources from multiple centuries confirm this, such as that from 1540 below.

Much later, in the mid-20th century, other ethnic groups like the Gurage invented some letters themselves.

These were quickly copied into Tigrinya, where they are still used.

Although most Aksumite and pre-Aksumite literature was inscribed on various objects—ranging from metal to stone—this practice was superseded by manuscripts, which are more portable and practical.

Today, scholars estimate that there are over 200,000 Ge’ez manuscripts and that virtually 99% of them were produced by Amhara scribes.8

They reached this conclusion based on the frequent and arbitrary interchange of different letters that had different pronunciations when Ge’ez was still a spoken language—namely:

ሀ in lieu of (ILO) ሐ and ኀ and ኃ

አ ILO ዐ and ዓ

ሰ ILO ሠ

ፀ ILO ጸ

This represents a guttural and sibilant reduction that occurred to such extent only in Amharic and serves as a major indicator of Amhara authorship.9

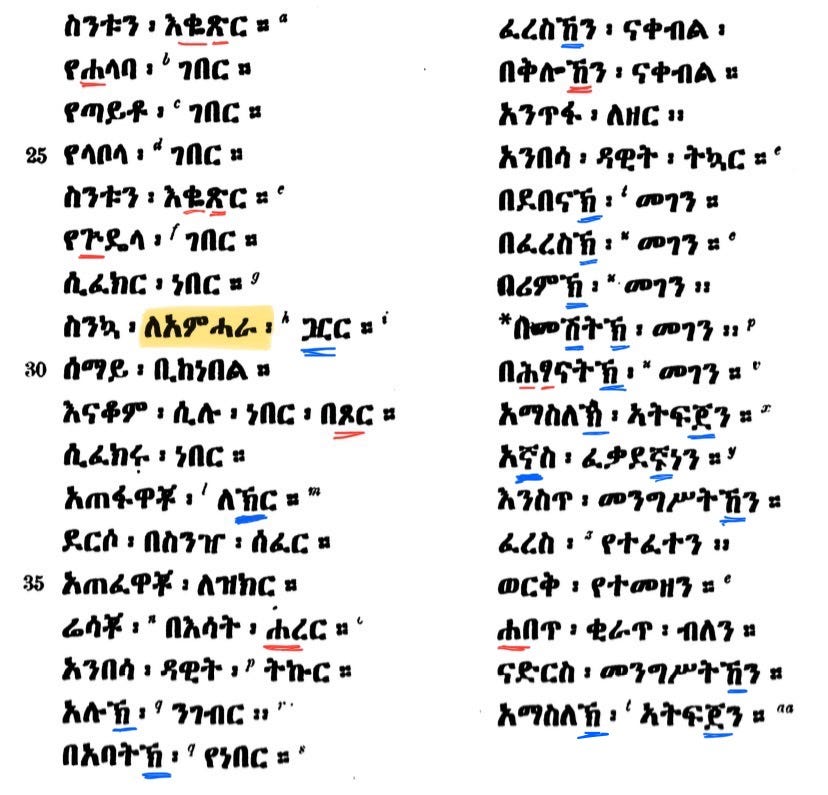

There are other clues, too. Take, for example, this 15th century manuscript called ውዳሴ አምላክ (wədase ʾäməlak ; Amharic and Ge’ez: “Praise of the Lord” ).

To the naked eye, it is a Ge’ez manuscript and nothing more. But upon closer inspection, one notices the profound Amharic influence on the writing.

In the above, red represents words with letters that originate from Amharic, such as በእጨጌ (bäʾəč'äge ; a Church title) and አዋጅ (ʾäwaǧ ; “decree”).

Green represents fully Amharic words, like አፄ (“emperor” ; ʾäs'e , instead of the Ge’ez ሐፀይ or häs'äy) and ሰጥቻለሁ (“I have given” ; sät'əčalähu , instead of the Ge’ez እሁበኩ or ʾəhubäku).

There is significant overlap between the two, which will be expanded on later.

The rise of Amharic

Amharic literature generally emerged in the 14th century.

The most commonly cited example is the contemporary Amharic victory poems sung for the Amhara Emperor ዓምደ ጽዮን (ʾamədä s'əyon) by his troops during their Crusades across East Africa and South Arabia. More on that later.

Another example is this 15th-17th century Amharic poem entitled መርገመ ክብር (märəgämä kəbər ; “Condemnation of Glory”).

Beyond permeating its literature, Amharic has also influenced the way Ge’ez is “spoken”—particularly in Church, where it remains the language of liturgy.10

By the last quarter of the 18th century, Amharic became an accepted alternative to Ge’ez. Chronicles of important figures like kings and saints—once written in Ge’ez—were superseded by Amharic, which allowed for greater flexibility in expression.

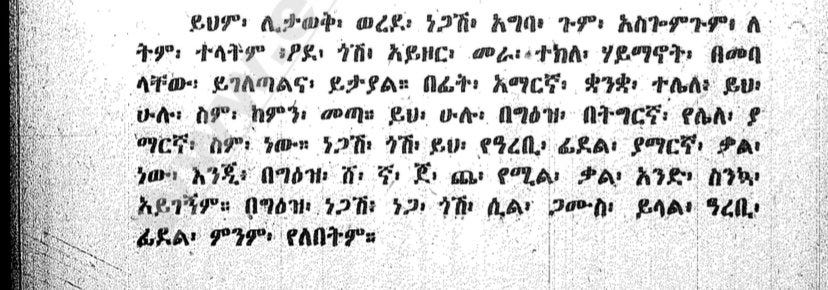

Most foreign correspondences and treaties were also conducted in Amharic, even in neighbouring Eritrea. The Amharic letter below, dated to 1869, is addressed to King Napoleon III of France.

It was written by Ras Welde Mikael Solomon, hereditary ruler of Hamasen, which covers most of the Eritrean highlands.

In 1855, Emperor Tewodros II made Amharic the official written language of government.

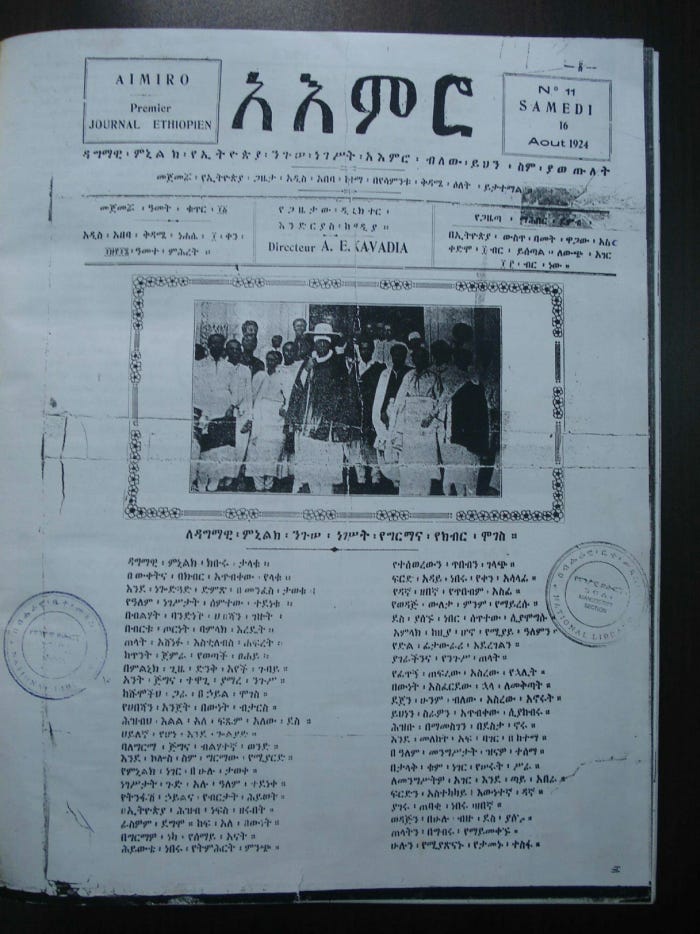

Amharic literature continued to flourish into the 20th century, with the earliest Ethiopian textbooks, advertisements, movies, novels, and more published in this kingly language.

According to Ethiopian Foreign Policy, the Amharic newspaper below, established in 1889, was the first African newspaper published in an African language. It had weekly issues and was popular both in and outside of Ethiopia.

The rise of Tigrinya

As a spoken language, Tigrinya emerged from late-Ge’ez some 1,000 years ago, specifically in the area of present-day Eritrea.11

There, the Kebessa ethnic group speaks the purest form of the language. A predominantly Muslim community known as the Tigre speaks a similar language, called “Tigrait.”

Because most Tigrayans speak Amharic as a second language, the Tigrinya used in Ethiopia is heavily diluted by Amharic.

This reality is illustrated by the primary source below. I will expand on it later, too.

Ironically, “Tigrinya” (ትግርኛ ; təgərəña) itself is an Amharic word. Speakers of this tongue do not have a unique nomenclature for languages, so they, like most Ethiopians, use the dominant Amharic system.12

Although some have suggested Tigrinya was first written in the 13th century—making reference to the “statues of Loggo Sarda and Cewa”—scholars have rejected these claims as baseless and ultimately false.

Indeed these texts written at the very end of the 19th century—not by native Tigrinya speakers but by European missionaries, scholars, and colonial officials.13

The earliest Tigrinya texts known to the world were likewise produced under European influence. Take, for example, the 1837 translation of the Four Gospels from various European languages to Tigrinya.

It was done by the half-Greek (paternal) and half-Agew “Matewos of Adwa” on behalf of European missionaries who sought to convert Tigrinya-speakers to Catholicism and Protestantism. Matewos himself converted to Catholicism shortly after the task.14

Another example is the Tigrinya customary laws of “Adkeme-Milgae,” completed—according to the first page of the manuscript—by Italian scholars in the 1930s.

Evidence of the foreign authorship of the document above comes from the widespread use of the letter አ (ʾä), which native Tigrinya-speakers always replace with ኣ (ʾa) as it better reflects how they pronounce the sound.

Another major textual cue, this time for the date, is the presence of the letter ቨ (vä), borrowed from English or another foreign language in the 20th century.

It was noticeably absent in the royal Amharic letters of Amhara Emperors Tewodros II and Yohannes IV in their addresses to Queen Victoria in the latter part of the 19th century.

In 1910, the Società Asiatica Italiana confirmed that Tigrinya had no literary form.15

After taking control of Eritrea by 1942, the British Administration published a Tigrinya newspaper, called Eritrean Weekly News. It was the first of its kind in the region.

In 1973, Ullendorff wrote that Tigrinya literature was still in its infancy, and that there was “very little original creation.”16

Amharic and Ge’ez: two sides of the same coin

As evidenced by the አገዘ inscription far above, Amharic writing existed some 2,000 years ago.

This is consistent with the findings of other scholars, which point to an Amharic originate date of at least 1,700 “years before present” (YBP).

However, Amharic was quite different in those days, and there is evidence to suggest it was once identical to proto-Ge’ez, or very close to it. Some proofs are below.

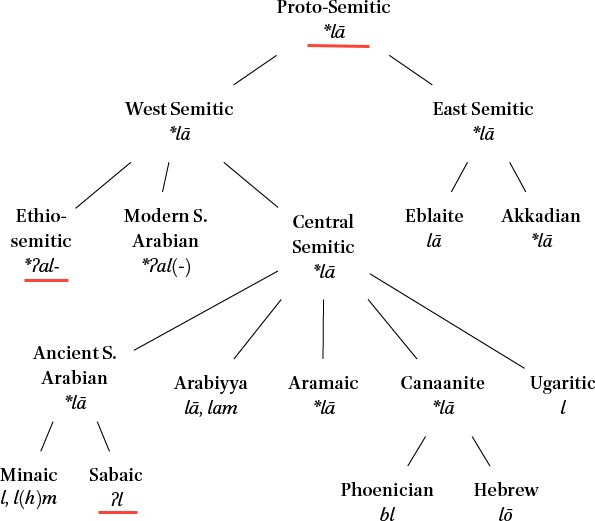

Negation.

The oldest Semitic languages negate words using the prefix “al” or the closely related “lo.”

a) In Amharic: አል (ʾäl) as in አልሄድም (ʾäləhedəm ; “I will not go”). Notice how the negator suffix is ም (m).

b) In Arabic: لا (la) as in لا أُحِبُّ الجَزَرَ (lā ’uḥibbu l-jazara ; “I do not like carrots”). This is one of several similar negators.

c) In Hebrew: אל (al) or לא (lo) as in אל נשכח (ʾl nškḥ ; “Let us not forget”). Two of three close negators.

d) In Akkadian: 𒌌("ul”). This was the chief negator in Akkadian.

e) Although late-Ge’ez uses ኢ (ʾi) to negate words, scholars agree this was አል (ʾäl) in proto-Ge’ez.

They reached this conclusion based on the negator (𐩲)𐩡 (“al”) in Sabaic.

Another indicator is the presence of negators like አልቦ (ʾäləbo ; “no, not, etc.”) and አኮ (ʾäko ; “not”), relics of proto-Ge’ez.

There is also አላ (ʾäla), heard in the Ge’ez prayer of Our Father, where it means “rather” or “instead,” both synonyms of “not” with respect to an alternative.

f) The main Tigrinya negator is ኣይ (ʾay) as in ኣይተሰብረን (ʾayətäsäbərän ; “He did not break”). The negator suffix is ን (n), like in various Cushitic languages.

Amharic is interesting for many reasons, one being that it can also use አይ (ʾäy) to negate words, such as in the 3rd person masculine form: አይሄድም (ʾäyəhedəm ; “He will not go.”).

Experts agree that in ES, the አይ (ʾäy) negator evolved from an earlier አል (ʾäl).17 It changed to due a process called “palatalization,” where sounds move closer to the hard palate (roof of the mouth) for easier pronunciation.

Hence, the ለ (lä) sound weakened and disappeared. What remained was አ (ʾä), which changed to አይ (ʾäy) via a vowel shift. Since አይ (ʾäy) already had a front vowel, it naturally evolved into ኢ (ʾi) through palatalization.18

A study of Aksumite inscriptions reveals that shortly after Ge’ez prevailed over Sabaic, palatalization had already occurred, and አይ (ʾäy) and ኢ (ʾi) negations were used interchangeably.

For instance, in the 1,600-year-old Ge’ez inscription below (RIE 189), made by King Ezana, the first negator in red is አይይቁም (ʾäyəyəqum ; “Do not stand”), almost identical to the Amharic አይቁም (ʾäyəqum).

Meanwhile the absence of negator አል (ʾäl) in Tigrinya is another indicator that it did not exist prior to palatalization in Ge’ez.

Vowel pattern [masc., 3rd-pers. sing., preterite; (“he killed”)].

a) In Sabaic: 𐩤𐩩𐩡 (qä-tä-lä).

b) In Amharic: ገደለ (gä-dä-lä).

c) In Ge’ez: ቀተለ (qä-tä-lä).

Notice how these all share the same ä-ä-ä pattern. It is attested in the 1,500-year-old Ge’ez inscription of the Amhara King Kaleb of Aksum below, detailing his reconquest of Yemen.

d) However, in Tigrinya, this becomes ቀተሎ (qä-tä-lo), breaking the tradition.

Imperfect (presence of a vowel between beginning consonants).

a) In Akkadian: 𒄿𒅗𒀸𒊭𒀜 (i-ka-ššad ; “he reaches/achieves/conquers”).

This is one that all ES under analysis share, more or less, with the above.

b) In Ge’ez: ይስብር (yə-sə-bər; “break”).

c) In Amharic: ይስበር (yə-sə-bär).

d) In Tigrinya: ይሰብር (yə-sä-bər).

Prepositions (“for” or “to” and “in” or “on,” respectively).

a) In Sabaic: 𐩡 (lä) and 𐩨 (bä). See the Sabaic inscription below, about 2,600 years in age and found in Somaliland. Part of it reads: 𐩨𐩣𐩧𐩫𐩨 (bämäräkäbä ; “on a boat”).

Also notice how the word for “boat” is the same in Amharic (መርከብ or märəkäb), like (alternatively) in Arabic مَرْكَب (markab). The Ge’ez equivalent is ሐመር (hämär). Yet, Tigrinya uses the Amharic term መርከብ with no changes to spelling.

b) In Ge’ez: ለ (lä) and በ (bä).

c) In Amharic: also ለ (lä) and በ (bä). See the document in proof (5) for both these examples.

d) In Tigrinya, this becomes instead: ን (n) and ብ (b).

Possessive [1st pers. sing. (“my”)].

a) In Ge’ez: የ (yä). This appeared, for example, in DAE 9 some 1,600 years ago as ብእስየ (bəʾəsəyä ; “my clan of…”).

b) In Amharic: also የ (yä). See the late 1800s Amharic letter below.

c) However, in Tigrinya: ኧይ ('äy) as in ኣምላኸይ (ʾaməlahäy). This varies at times but is never the same as in Amharic and Ge’ez.

Preterite (1st pers.).

In general, the suffix for words in this form in both Amharic and Ge’ez is ኩ (ku).

Ex: “I wrote.”

a) In Ge’ez: ጸሐፍኩ (s'ähäfəku), as seen on the 1,100-year-old Aksumite inscription below, made by the Amhara Hatsani (“warlord”) Daniel.

b) In Amharic: the same as in Ge’ez (ጻፍኩ ; s'afəku), minus the guttural.

c) However, in Tigrinya this becomes ጽሒፈ (s'əhifä). Moreover, the root of this word is different in the closely related Tigrait language, suggesting it was borrowed into Tigrinya from Amharic.19

The big question

“If Amharic is the direct descendant of Ge’ez, why is Tigrinya lexically closer to Ge’ez than Amharic?”

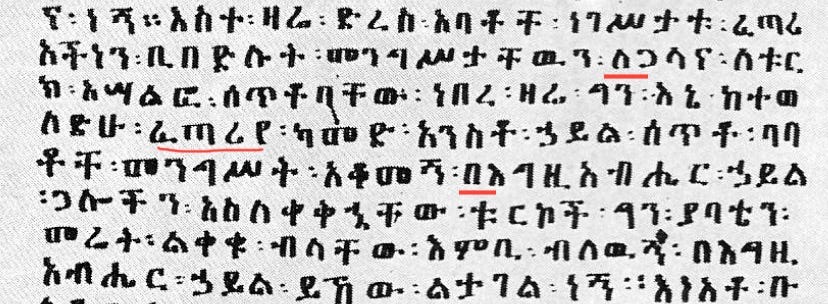

On the contrary, a study of Amharic writing over the centuries shows that, until the 17th century, Amharic was the closest to Ge’ez—lexically and textually. Hence, any claim to the contrary owes but to a modern phenomenon.

For this, we have evidence from early Amharic writings, which I expand on in reason (3).

To answer the question, though:

Tigrinya (and late-Ge’ez) is a very young language.

A direct consequence of this, as hinted throughout, is that the majority of Tigrinya must, naturally, descend from this later form of Ge’ez.

This helps to understand why one study found (out of a moderate word bank) only 15 Semitic words present in Tigrinya that do not also exist in Ge’ez.20

Meanwhile, the number of Semitic words present in Amharic that do not exist in Ge’ez is far, far higher.

Many of these are cognates with Hebrew, leading experts like Wolf Leslau to suggest that Amharic shares the closest relationship to Hebrew of any other Semitic language.21

However, others lack cognates in most Semitic and Cushitic languages, because they are purely Amharic inventions.

I say “inventions” because Amharic, more so than Tigrinya, adopted new sounds from neighbouring languages—sounds which, as you saw further above, did not exist in Ge’ez or its forerunner.

The result was new words that did not exist in other ES languages until borrowing from Amharic, which I explain more in reason (2).

To digress, despite insinuations that the absence of some gutturals in Amharic is indicative of a “non-Semitic” or “non-Ge’ez” origin, all ES languages are influenced by other, particularly Cushitic, languages.22

Nevertheless, Amharic retains an impressive closeness to Ge’ez.

A study of 100 words from various ES languages produced the following results: Amharic (62%), with Tigrinya not much higher (68%), and Tigre (Tigrait) the highest (71%).

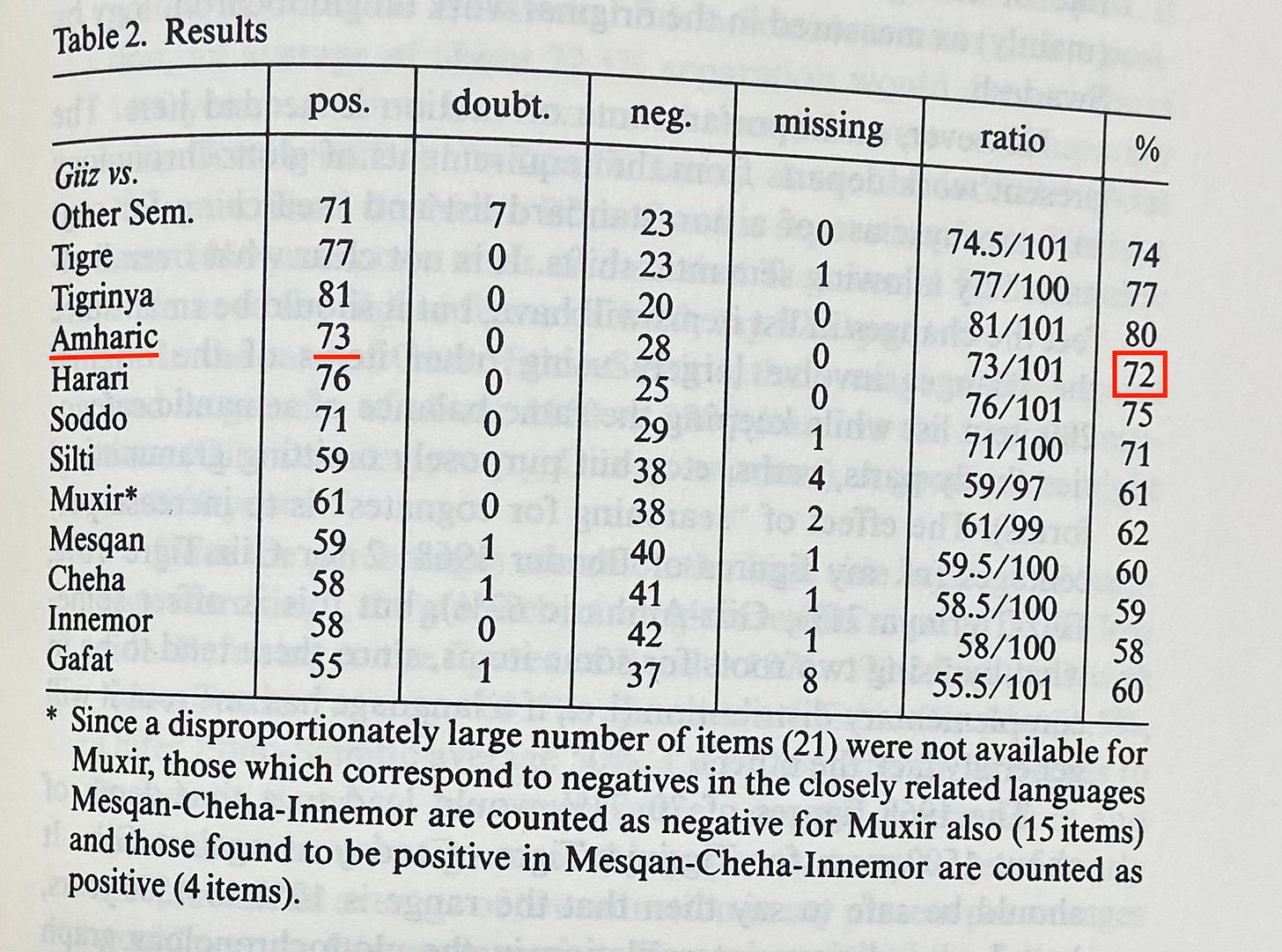

Another study conducted some years later by the same scholar produced different results.

Note the following:

(1) The results are wildly different, especially for languages like Hararinya (Harari), which jumped from just 53% closeness with Ge’ez in the first study to 75% in the second—higher than previous results for both Amharic and Tigrinya!

(2) Ogaden Arabic supposedly shared 40% closeness with Ge’ez in the first study, but it was not even considered in the second.

(3) Drawing on the work of Paul Black (1973), Bender concludes that “a difference of 9 points is required to achieve a confidence level of 20% that the result is statistically significant.”

Because Amharic sits at 72% and Tigrinya at 80%—an 8-point difference—by most standards, the two are “indistinguishable as far as synchronic lexical resemblances to Ge’ez are concerned.”

For some time, it was also hypothesized that Amharic had only a small number of Semitic roots, and that it “borrowed many roots from Cushitic.”

However, a 1979 study of 2,000 Amharic words revealed that less than 1% of the Amharic lexicon is derived from Cushitic.23

In fact, about 73% of Amharic words with identified roots were Semitic in origin. In the textual analysis, this figure jumped to over 75%.

As to Cushitic influence on Amharic syntax, one scholar put it as follows:

Ge’ez is the only Ethiopian language which preserved the old Semitic syntax and was but superficially affected by [Cushitic influence]. The northern most living language, Tigre, is much less rigid in word order than the rest, and it may optionally have either the Semitic pattern or the Cushitic one. All the remaining languages have exclusively a Cushitic-type word and system. This suggests that the Cushitic influence affecting syntax came later and was independent in the different branches of [Ethio-Semitic].24

To illustrate this, behold the following table, which shows that Amharic and Tigrinya generally have the same sentence structure, one that is different from Ge’ez.

Based on the information above, I have created the following pie chart.

Tigrinya has lacked a written form for most of its history.

This has limited the development of a lexicon unique to Tigrinya, which relied on loanwords from Ge’ez to sustain it over the centuries.

An indirect consequence of this has been that many Tigrinya words beginning with Amharic letters are borrowed—you guessed it—from Amharic.

For instance:

ዳኛ (daña ; “a judge”)

እንጀራ (“ʾənəǧära ; “Injera,” a staple food)

ጨው (č'äw ; “salt',” a cognate with various Cushitic Agaw languages)

አሸንዳ (ʾäšänəda ; a sort of drainage pipe but also the name of a popular festival)

Likewise, because Ge’ez has been “relegated” to religious usage for so long, it became—as one scholar put it—“lexically impoverished in Semitic fields having to do with technical details of farming, hunting, warfare, metal manufacture, carpentry, etc.”25

Guttural retention.

In the 14th century Amharic poem below, sung for Emperor Amde Tsion, we see far more gutturals and sibilants than exist in modern Amharic.

These are, to put it bluntly, the “nasty throat sounds” heard in the more “rough” Semitic languages but also various Cushitic languages.

For instance:

In the Ge’ez Our Father, one says:

ትምጻ መንግሥትከ (təməs'a mänəgəśətəkä ; “Thy Kingdom come…”).

Ignoring the different sentence structure, this became: መንግስትህ ትምጣ (mänəgəsətəh təmət'a") in Amharic.

Hence, the sibilant was weakened to go from ሥ to ስ and from ጻ to ጣ .

Why is this important? Because it is these “throat sounds” that form the basis of many lexicon comparisons.

Due to their removal from Amharic (generally), some foolishly assumed words that lack the guttural or another “rough” sound could not descend from those that retained it.

One fellow had even claimed that only 1% of Amharic could descend from Ge’ez on this basis alone………….

Yes, absurd, especially when considering important names, such as “Amhara” itself.

In Ge’ez (and Old Amharic, like in the poem above), it is አምሓራ (ʾäməhara). But today, the guttural ሓ is removed and it is simply አማራ (ʾämara).

Now, do these words have separate origins? Clearly not—and this is the case for many Amharic terms today, meaning the “guttural standard” used by a fringe to compare ES languages is deeply, deeply flawed.

Conclusion

Since it is such flawed standards on which these comparisons are made, any study that compares Amharic, Ge’ez, etc. ought to do so by accounting for Amharic’s unique path amongst ES languages, lest the results be dubious…… and historically challenged.

Fortunately, as Gebremariam explained a century back, and as most evidence shows:

“Amharic existed long before the time of Yekuno Amlak. But the emperor was the first to retire the nasty throat sounds of Semitic speech, yielding a beautiful, smooth language fit for royals.”26

So although Tigrinya’s retention of these unpleasant sounds has enabled it to be negligibly closer to Ge’ez, it has also cursed it to negative perceptions in Ethiopia and beyond.

The situation is so grave that many Ethiopians hurl insults like ፂላ (s'ila) at the Tigrinya-speaking community, in reference to the ፅ (s') sound they, like birds, seemingly make.27

Thankfully, most Tigrinya-speakers have good exposure to Amharic nowadays, and their language is, just like Amharic some time ago, phasing out unwanted sounds, as evidenced by the change in Tigrinya from the ነጽሐ (näs'əhä ; “free”) still used in Ge’ez to the Amharic ነጻ (näs'a).

Another example is the shift from ሓርበኛ (harəbäña ; shared with Old Amharic to mean “patriot”) to ኣርበኛ (ʾarəbäña).

As Tigrinya continues to evolve closer to Amharic, it will one day gain the respect it deserves as a member of the ES family.

Thanks for reading! If you appreciate my work, consider supporting me at any of the links below. Until next time,

-EM

Recluse, Élisée. (1892). “The Earth and Its Inhabitants,” Vo. 1, p. 152.

Kitchen, Andrew et al. (2009). “Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East,” p. 2706.

Lipinsky, Edward. (1997). “Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar,” p. 81.

Butzer, Karl. (1981). “Rise and Fall of Axum, Ethiopia: A Geo-Archaeological Interpretation,” p. 492.

Durrani, Nadia. (2001). “The Tihamah coastal plain of South West Arabia in its regional context: c.6000 BC-AD 600,” p. 307.

Ullendorff, Edward. (1951). “The Obelisk of Matara,” p. 29.

Dillmann, August. (1853). “Zur Geschichte des abyssinischen Reichs.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. Vol. 7, pp. 338–364.

Uhlig, Siegbert et al. (2017). “Ethiopia : history, culture and challenges,” p. 170.

Weninger, Stefan. (2011). “The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook,” p. 117.

Lipinsky, op. cit., p. 90.

Woodard, Roger. (2008). “Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Aksum,” p. 212.

Kievet, Dirk et al. (2013), "The Semitic languages: An International Handbook," Vol.

4, p. 1170.

Duncanson, Dennis. (1949). “Sir'at 'Adkeme Milga'. A Native Law Code of Eritrea,” p. 142.

Smidt, Wolbert. (2010). “Matewos (First Tigrinya Bible Translator, 19th century),” in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol 5., p. 421.

Società Asiatica Italiana, Florence. (1911). “Giornale della Società Asiatica Italiana,” Vols. 23-24, p. 2.

Ullendorff, Edward. (1965). “The Ethiopians: An Introduction to the Country and its People,” p. 127.

Pat-El, Austin. (2012). “On Verbal Negation in Semitic,” pp. 22-23.

Sjörs, Ambjörn. (2018). “Historical Aspects of Standard Negation in Semitic,” pp. 339-340.

Littmann, Enno and Hofner, Maria. (1972). “Worterbuch Der Tigre Sprache,” p. 414.

Yemane, Teklehaymanot. (2017). “Semitic Words Found in Tigrigna but not in Ge’ez,” p. 75.

Leslau, Wolf. (1975). “Amharic Parallels to Semantic Developments in Biblical Hebrew.” Also see “Hebrew Cognates in Amharic (1969)” by the same author.

Zaborski, Andrzej. (1991). “Ethiopian language subareas,” in Stanistaw Pitaszewicz and Eugeniusz Rzewuski (eds.), Unwritten Testimonies of the African Past, p. 123.

Appleyard, David. (1979). “A Statistical Survey of the Amharic Lexicon,” p. 77.

Hetzron, R. (1972). “Ethiopian Semitic: Studies in Classification,” p. 19.

Yemane, op.cit., p. 60.

ታየ፡ገብረ፡ማርያም፡፲፱፻፲፬፥የኢትዮጵያ፡ሕዝብ፡ታሪክ፡ገጽ፡፳።

Barrach-Yousefi, Nicola and Middleton-Detzner, Althea. (2021). “Hateful Speech and Conflict in the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia,” p. 36.

Keep it up! we Amharas need people like you tarik melalsh

Very informative! Thank you